Slowly the list of books is being added and I am approaching a book that was actually published, The Driftless Zone, which I never conveniently forget was an afterthought, something akin to a sabotaged serendipidy, like a nonpareil one night stand that ends with liquor and smokes available in the morning but the thought to write down an address, a phone number, a witness, arises only after she has left. So begins the serious divide between two whisps of persona, not to mention a series of expectations that were the necessary playing field for my own particular encounters with specific visitations of the absurd.

Monthly Archives: February 2015

Contact Rick Harsch

rick.harsch@gmail.com

if buying a book, please pay in person, through an emissary or liaison, ‘paypal’, or a ‘known associate’.

All contacts are guaranteed to be entirely prophylacticized.

Books by Harsch

The Stupid Persistence of Inanimate Things, or, Carcass of the Known Self

I wrote this beginning in the latter part of 1988, finishing in early 1990. If my memory is correct, I wrote most of it on French Island, the island in the Mississippi where I worked as a security guard at a power plant. It is not a Bildungsroman. Probably it would best be described as a state of the author as early clochard, low morals and high ideals.

Status: In line to be typed into a computer/unavailable unless you come to my apartment to read it.

Taxi Cabaret: The Adventures of a Fat Nihilist

Status: Being typed into a computer/unavailable unless you come to my apartment to read it.

The Appearance of Death to a Hindu Woman

Status: Available in word format or PDF, free or with donation to the author. I’ve sent it free often, so there is no need to feel lousy about asking for it and not donating. At the same time, if you have a lot of money and don’t give a shit about reading, or at least not this particular book, there is no limit to the amound you may donate.

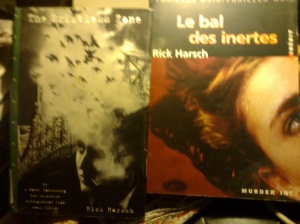

The Driftless Zone

Status: Available used, but not from me. Amazon may have some new copies in stock, but officially the book is out of print and I own the rights (along with one copy from the original printing and a copy of each its French incarnations).

For an early review of the book, here’s a link: http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-883642-32-7

Published in hardcover in 1997, paperback the next year, translated into French, where it was presented in two different formats before the French Publisher (Murder, Inc!) went bankrupt. Several years ago the book went out of print. Steerforth Press, the publisher, had promised never to take any of their books out of print, but they reneged, presumably in a good faith effort to survive. When a book is taken out of print it is either industry practice or law that before the books are taken out and burned they must be offered to the author at a dollar per book. Steerforth therefore asked me how many copies I was willing to ‘buy’. Foolishly, I said 75 of each (the two others with The Driftless Zone form a trilogy), but as the books were on their way from Vermont to Slovenia I had time to think the situation over and decided that I would simply take the books and refuse to pay. This is no reflection on Steerforth, whose survival is a good thing for US publishing, rather on the bizarre nature of the circumstance a commercial failure of a writer is in because books have become too expensive to warehouse (thanks to the Reagan administration). so Steerforth is out $225, but I should have asked them to send all the books…

Billy Verite

Status: Available used, but not from me. Amazon may have some new copies in stock, but officially the book is out of print and I own the rights (along with one copy from the original printing and a copy of each its French incarnations, same as with The Driftless Zone).

Here’s a review: https://www.forewordreviews.com/reviews/billy-verit/

Here’s another review: http://www.sfgate.com/books/article/Unlikely-Hero-Battles-Evil-From-His-Island-2954122.php

I thought that cover would sell enough books to make up for my $5000 advance, and so did my publisher. Unfortunately, the book came out at the same time as several fat books by bigger names–I think Pynchon was one, and DeLillo…So we needed a good review from the New York times to get any attention. As you can see from one of the links above, the San Fran Chronicle liked it, but the book came out on September 1, 1998, and the review came out in, I believe, January of 1999. Steerforth Press’ publicity guy took the book to the Times and got the editor to read it. He said the editor liked it a lot, so we eagerly watched for the review to appear, and it never did. The likely conclusion is that he sent to someone who gave it a bad review and since he liked it he tossed the review so as not to do me and Steerforth damage.

Nonetheless, it was a happy book. When my editor called to say he liked it he kept calling the protagonist ‘Stinkin Billy’…The night of that phone call, I went to the Casino pub in La Crosse, WI, and bought some drinks for one of the other characters, a friend of mine who failed to survive as a character, but was still able to drink lavishly.

The book also provided some laughs for me as it provided the opportunity to thank the Iowa Writers Workshop and congratulate them on their stewardship of the Michener Foundation’s award program. When you get a Michener you have to agree to mention them in the book, or before or after the book, so I did:

‘I received what’s called a Michener/Copernicus Award for this novel–twelve grand in small, unmarked bills, delivered in twelve monthly payments to prevent me from investing unwisely–and I’m thankful to the Michener Foundation and the University of Iowa, especially now as I write because I have another six months of this literary swag coming. However, as is generally the case with awards, this came long after the book was finished and so did nothing to lift me from the circumstance of wretched dependence I was in while writing it. It seems more important, therefore, to thank, with the help of an exhaustive list, those who provided me aid when I needed it:’

There followed a precise list of those who gave me money and how much they gave: 13 people, their gifts totalling $1605 over a four month period. Then I listed 29 people who gave me food and or drink, 9 who gave me clothing, and 11 who gave me literary advice.

A couple of years later, in the morning, on a weekday, I received a phone call from that goofball Frank Conroy who ran the writers workshop and controlled the Michener funds, who did so corruptly–this is no idle accusation, but the details aren’t terribly interesting, and now, as he put it, wanted me to return the money because I had not been nice about getting the award. I recall saying, but gosh, Frank, I think I spent it all…

Later, as my career failed to careen, my editor said he never should have allowed me to do what I did, but I enjoyed it too much to agree and really think it had no affect whatsoever on my writing life.

The Sleep of Aborigines

Status: Out of print. Maybe available on Amazon new. Available at used book stores. I have about five copies in English, one in french (terrible cover).

Here’s where the career turned bad. The book itself was, for me, the best of the three. I had a vision of it that turned out precisely right. I ended the trilogy in the one sure way it could be ended–I killed off Rick Harsh, and the I that coursed through the books, which could be the Rick Harsch, also departed in what I consider the best of my closing paragraphs of the trilogy. I was disappointed in the silence that followed Billy Verite, but not discouraged, and expected that after publishing a third novel in three years I would make a smooth transition to a different landscape.

The first problem was that my editor envisioned something bigger than what I wrote, longer, more all-encompassing, something like that. We discussed it, and he came out of our discussion congenial and prepared to support this book. But he had to edit it. And he was an excellent editor. He was a friend of Hunter Thompson, which suggests a certain wildness and sense of freedom, and both were true. But before he could edit the book he became what used to be called clinically depressed. It was worse than that sounds. I joked occasionally that my book brought on his depression. And that may be true for all I know. At any rate, it took him more than two years to finally edit the book. It took so long that the publishing house decided that they would simply have to drop the book. Naturally, I nearly went insane. My agent came to my rescue with a horseshit compromise: the book would come out in paperback (and therefore largely be ignored–in the publishing world it is a kind of defeatism, or, it is a small press that only publishes paperbacks to keep prices down; either way, a paperback original faces a difficult battle which mine lost rather quickly). The book received few reviews. Here’s one of them: http://www.fictiondb.com/author/rick-harsch~the-sleep-of-the-aborigines~92667~b.htm

I have no idea where it really came from.

So ended the trilogy. I am happy with it overall because of the people who read all three books most had a clear favorite and they spread fairly evenly.

The Skulls of Istria

Finished in 1999 or 2000

Status: available in Slovene or in PDF in English.

Serious troubles with my agent dogged me before I finished this. At first he liked it, but then we had what I would consider a minor row, but that forever changed his view of me. By the time I finished this book, he was jaundiced, and all communications about The Skulls of Istria showed this. He didn’t understand it, he said. And so on. He claimed he tried to sell it but I am pretty sure he never sent it to a single publishing house. So now it is available in a Slovene translation only.

Voices After Evelyn

Finished in 2001.

Status: PDF…working towards an eventual US publication. Perhaps the odds are 50/50.

What I considered my most conventional novel, a novel told in many voices (hardly a groundbreaking tactic), my agent told a mutual writer friend that it was too experimental. The friend mentioned As I Lay Dying. Never mind, the agent was looking for a way out. He said he didn’t get the ending and that if he didn’t no one would. The ensuing conversation ended our collaboration.

Adriatica Deserta

Finished in 2001

Status: same as Skulls of Istria

Requiem for a Suicide

Finished in 2003

Status:

This book cannot be published without two accompanying novels, Balkan Picaresque and A Hand in Amber, Darkly, neither of which is finished, probably (Balkan Picaresque is perhaps finished in long hand; I’ll know when I put it on computer). The three together will be called the Requiem Trilogy. Requiem for a Suicide is an idyll that takes place on the shore of Sloven Istria, somewhat near to the tavern in Piran where Joyce fucked his eyes and The Skulls of Istria is told. The end of that book meets the end of Balkan Picaresque–either may be read first–and the two conflue into A Hand in Amber, Darkly, which finally gives full floor to the character Kacper Barczek, a mad Pole. Skulls of Istria is well-connected to Requiem for a Suicide, but discretion prevents me from elaborating. When I finish the novel I am currently working on, The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas, which I plan to be the last novel that takes place in the US, I will finish these, before or after revising A Circumnavigation through Maritime History.

A Circumnavigation through Maritime History

Finished in December, 2007 or 2008, it’s difficult to remember.

Status: Unpublished, available from me in word or maybe PDF. Likely to have a few chapters added on when the current novel is finished or sometime thereafter. Despite its status, there is a marvellous review of the book by a seafaring feller who read the book in its current form: http://www.macumbeira.com/2012/06/circumnavigation-through-maritime.html

This book resulted from my work with the maritime school in Slovenia where I worked for about seven years. As the English department was coming under assault from the hinterlanders of the school (traffic, so maritime,and the subgenera logistics), a department of four and a half souls eventually reduced to one and three elevenths or so, we of English were told that we could offer optional courses. I was the only one to take up this offer or option, designing a course that would be called maritime heritage, and would be taught to seniors primarily, to further their English skills while putting their future trade into some kind of interesting context. I only needed approval from the maritime department, the chair of which only asked what books I would use. I told him I would write one. The answer then was yes, go right ahead. I spent the next year and a half acquiring numerous books, some with university money (they want me to return these books now: HAH!), reading reading reading, and after a year writing for about six months. I finished just when the university senate expected me too and so of course the university published the book…right? No. As it turns out, the offer for us to offer English elective courses was not meant to be taken up and through some Chicago-like backroom politics the universtiy publishing committee was first altered in composition and then intimidated into delaying publishing my book, and finally some lies were spread that if true would mean I was not qualified to publish the book (I had already co-authored a text at this same university–it’s called Routes to Traffic English; I don’t mention it in sequence above because it’s a simple text, co-authored, and of no interest to anyone but perhaps a handful of English students in Slovenia). Oddly, the course I designed resisted efforts to remove it from the university curricula and so is now taught by a Slovene maritime professor on an out-patient basis.

If I am not bitter perhaps it is because I limited the book to a degree because it would have had to have been read in a semester by my students, while now I am free to expand it. What’s there is there and won’t be re-examined to any degree, but I plan to add three chapters, maybe four it I get up the gall to write about Vikings. I’ll add a chapter on Venice, one on the Black Sea, and one on ports in general.

Kramberger with Monkey

finished in 2011 probably, published in Slovene translation 2012

Arjun and the Good Snake

Status: Available in hardcover in English, paperback in Slovene. The Hardcover is 24 euros and the paperback is 15 euros. Both have photos, in color in the hardback.

The subtitle of the book is Being an Ophidiological Account of Six Weeks in India Without Alcohol, which more or less sums up the book, apart from the parental aspects. After some months or years of sporadic trouble with drinking and social norms, enforced austerity and drinking, unfortunate encounters with large men with small empiires and drinking, men with knives and drinking, the married fathering life and drinking, I decided that on a family trip to India I would not drink, and instead would, in writing, give a little thought to all of the above. It was a good idea. I filled two notebooks during that time, discovered coconut demon mask art, read vorciously, ate the spiciest food on the subcontinent, careened about Chennai in autorickshaws with the book’s eponym, my son, and spent the next several months typing the book into a computer, adding paragraphs as they reared unfortunately to such necessity, in the end making a book that I thought might compare well with Fred Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, probably the only time I wrote something I felt I could authoritatively compare with a specific other book.

I found a publisher in Ljubljana, who agreed to publish the book first in English, both of us thinking that if we could get the thing into the US it would sell well. But to do so required warehousing he could not afford, or getting on Amazon, which is impossible with bank accounts mired in Slovenia. The story of trying to sell the book to a publisher in the US would be called Agent Reprise, and is partly told in the book and ends without a publisher ever seeing the book.

Kramberger z opico 10€

Published! Available only in Slovene or through the author.

Adriatica Deserta 19€

Istrske lobanje 17€

Chronologicals

So I am beginning to log in, blog in, my novels. The third novel was The Apperance of Death to a Hindu Woman, which not only was able to creep onto computer but also was ‘bought’ by an Indian press – ‘Indialog’ – that later dropped it when after two–2–editing sessions covering a mere 17 of its 250 or so pages, I appeared inflexible to them. This novel will be made available here to anyone who wants to read it. I have it in word format, will try to figure out how to get it into PDF, and will give it free to those who want it, and sell it to those who want to donate to a writer living in austerity economical conditions in Slovenia. This I say not to pressure readers to donate, rather to describe local conditions. I eat every day, as do my children, but it is rather too close a thing. So I will speak much of austerity economics, while offering books unbound for free or donations.

see Books by Harsch

1 FUCKING KENO [Hole card: 5 of hearts] He had been away from the States a mere four months and still the first cliché upon landing came as a gutsucking culture shock left hook beneath his guard, catching the sharp point of his lowest rib on the left side. ‘If you don’t like the heat, don’t come to Los Angeles in the summer.’ Le nausee. If you don’t like clichés, don’t return to the U.S. Seasons need not apply. And right outside the baggage claim, one step into the air, fresh fucking Mediterranean climate air, before his first cigarette in 19 years that seemed like 17 hours or vice versa, emphasis on versa. Then it was Vegas. Not even a week later. The cab driver kept his mouth shut, spending seven minutes ripping across thoughts to the strip, where the welcome drive of the Luxor yielded seasonal palms and shockingly familiar terra cotta Egyptiana. The room was waiting. What else could a room do? Eddie tossed his suitcase on the bed, sucked a vodka from the mini-bar, drank it in a fluidity of gesture derived from 19 years of not giving a shit for externae. Then he walked to the World’s Biggest Gift Shop at the far end of the strip, bought a deck of cards, some dice, and a Vegas shirt with such paraphernalia scattered in a decipherable yet black background design and walked back to the hotel, where he plucked a vodka from the minibar and drank it with a fluidity suggesting a smooth cool desert generated drink, before trying on the shirt, looking at the mirror where he noticed himself, and pronouncing out of the muck of mutter, “Fucking keno,” with disgust. 2 FUCKING KENO [Hole card: 3 of clubs] Fucking kid was right about everything but one—he was dead fucking wrong the way he blamed Gravel. Gravel’s fault? Sure, but had he not just blamed him, had he hit him in the head with something like a fresh tempered axe, it would have all been okay. But no. And there he was. Vegas. Vegas and the clichés. First thing even before he picked his room, stepping into the fine feathers of the desert air outside the motel some shitbird in a Hawaiian shirt and the grease sweat of a bad eater was slinging the lowdown: ‘If you don’t like the heat, don’t come to Vegas in the summer.’ Worst of all, he said it with a lilt rising at the end, like a pimply ice skater coming to the beaten down beatifice halt on the toes of the skates before the Rachmaninoff was ready to recede. Nobody’s dreams were on the line. Already in his kid’s distressed goatskin, tegu lizard inlay boots. Gravel was Eddie Vegas’ reaction. And he didn’t even have a gun. Round up the goats and what? Imagine play waltzes. Over and over again waltzes. Not the same one, but the same one seventeen times in a row and then cross them up with something heavy on the horn. Ship the lizards from some German in Paraguay, where it doesn’t matter if they’re legal or not. Stroessner goats. No doubt it could not be stranger than that. And somewhere between Nogales and Cuernavaca, Peedro is teaching his son the same trade. The easy part is keeping your mouth shut for years at a time. The motel he had finally pulled into after going vacant of mind and cruising in enclosed geometries for a half or few hours was called The Electra Glide, no mention of gambling whores or wifery. He slid his suitcase onto the narrow bed, slept the dark out, and went down to the front desk to ask after the nearest bar and the World’s Biggest Gift shop. “Bar’s out back, faces the parallel street. Gift shop even easier: That corner and the next, make a right and you’re there.” You’re there was seven city blocks in 107 degrees. Gravel bought a Vegas shirt: he liked the black background. The beer was well-deserved, but the heat had reduced his one need to a fucking Corona, with lemon inside and on the side. He stared at the shank while he ordered, he stared at the shank while he waited, and he stared at the shank while he slowly squeezed the lemon, that spurted nonetheless, into his glass, just 2 bucks for about a .33 glass. As he guzzled like a fucking cowboy he caught himself in the slant of light that made him electric in the mirror. Keno cards. “Fucking keno,” he said aloud.

1 FUCKING KENO [Hole card: 5 of hearts] He had been away from the States a mere four months and still the first cliché upon landing came as a gutsucking culture shock left hook beneath his guard, catching the sharp point of his lowest rib on the left side. ‘If you don’t like the heat, don’t come to Los Angeles in the summer.’ Le nausee. If you don’t like clichés, don’t return to the U.S. Seasons need not apply. And right outside the baggage claim, one step into the air, fresh fucking Mediterranean climate air, before his first cigarette in 19 years that seemed like 17 hours or vice versa, emphasis on versa. Then it was Vegas. Not even a week later. The cab driver kept his mouth shut, spending seven minutes ripping across thoughts to the strip, where the welcome drive of the Luxor yielded seasonal palms and shockingly familiar terra cotta Egyptiana. The room was waiting. What else could a room do? Eddie tossed his suitcase on the bed, sucked a vodka from the mini-bar, drank it in a fluidity of gesture derived from 19 years of not giving a shit for externae. Then he walked to the World’s Biggest Gift Shop at the far end of the strip, bought a deck of cards, some dice, and a Vegas shirt with such paraphernalia scattered in a decipherable yet black background design and walked back to the hotel, where he plucked a vodka from the minibar and drank it with a fluidity suggesting a smooth cool desert generated drink, before trying on the shirt, looking at the mirror where he noticed himself, and pronouncing out of the muck of mutter, “Fucking keno,” with disgust. 2 FUCKING KENO [Hole card: 3 of clubs] Fucking kid was right about everything but one—he was dead fucking wrong the way he blamed Gravel. Gravel’s fault? Sure, but had he not just blamed him, had he hit him in the head with something like a fresh tempered axe, it would have all been okay. But no. And there he was. Vegas. Vegas and the clichés. First thing even before he picked his room, stepping into the fine feathers of the desert air outside the motel some shitbird in a Hawaiian shirt and the grease sweat of a bad eater was slinging the lowdown: ‘If you don’t like the heat, don’t come to Vegas in the summer.’ Worst of all, he said it with a lilt rising at the end, like a pimply ice skater coming to the beaten down beatifice halt on the toes of the skates before the Rachmaninoff was ready to recede. Nobody’s dreams were on the line. Already in his kid’s distressed goatskin, tegu lizard inlay boots. Gravel was Eddie Vegas’ reaction. And he didn’t even have a gun. Round up the goats and what? Imagine play waltzes. Over and over again waltzes. Not the same one, but the same one seventeen times in a row and then cross them up with something heavy on the horn. Ship the lizards from some German in Paraguay, where it doesn’t matter if they’re legal or not. Stroessner goats. No doubt it could not be stranger than that. And somewhere between Nogales and Cuernavaca, Peedro is teaching his son the same trade. The easy part is keeping your mouth shut for years at a time. The motel he had finally pulled into after going vacant of mind and cruising in enclosed geometries for a half or few hours was called The Electra Glide, no mention of gambling whores or wifery. He slid his suitcase onto the narrow bed, slept the dark out, and went down to the front desk to ask after the nearest bar and the World’s Biggest Gift shop. “Bar’s out back, faces the parallel street. Gift shop even easier: That corner and the next, make a right and you’re there.” You’re there was seven city blocks in 107 degrees. Gravel bought a Vegas shirt: he liked the black background. The beer was well-deserved, but the heat had reduced his one need to a fucking Corona, with lemon inside and on the side. He stared at the shank while he ordered, he stared at the shank while he waited, and he stared at the shank while he slowly squeezed the lemon, that spurted nonetheless, into his glass, just 2 bucks for about a .33 glass. As he guzzled like a fucking cowboy he caught himself in the slant of light that made him electric in the mirror. Keno cards. “Fucking keno,” he said aloud.  3 THE HAND MADE VISIBLE Donnie [Hole cards: 5 of diamonds, 5 of clubs] 10 of spades Drake [Hole cards: ace of diamonds, king of diamonds] 6 of diamonds Others, high card showing: ace of spades. Bet: $15$. Called all around. Next card: Donnie: 5 of spades Drake: king of clubs Others, high hand showing: ace of spades, ace of clubs, six of spades Bets: $15$ called by Drake, raised $5$ by Donnie, called by double aces and Drake, three others dropped. Fifth card: Donnie: king of spades Drake : ace of hearts Big hand: 7 of hearts Bh bets: $15$, Donnie raises after Drake calls, Bh tosses in five, a look on his face as if yet again, yet again, a hedgehog dashed across the table without upsetting the peanuts the three who dropped are fracking at, their hands coon hands. Sixth card: Donnie: 5 of hearts Drake: 10 of diamonds Bh: “Deuce, fucking deuce! Deuce of shit, deuce of my fucking asshole, deuce of the fucking Margrave of Malzovia, deuces of the long knives. Deuce deuce and deuce fucking attorneys at law. Deuces don’t even have a suit, deuces don’t fucking, deuces fucking, deuces are my balls, this fucking hand is a fucking scrotum…fuck it, I’m out.” “Guess it’s my bet. Fifteen. You raise five…Enough of that shit. We start with $25$.” “Raise five.” “Fuck?” “Fuck? Raise five?” “Raise five.” “Raise…Fuck you: raise twenty-five.” “Twenty limit.” “Right, forgot. Twe-” “Sallright: twenty-five and five.” “Okay, so what’s the limit now, smartasss? Who let this fuck in the game?” “You did.” “I know. Fine. Twenty-five limit. So there goes another trust fund. No fucking transmission of disease. They call it a disease, but ask anybody at this table, you rather have gonorrhea or an empty bank account…Twenty-five.” “Raise five.” “Fuck you: twenty-five.” “Raise five.” “Twenty-five.” “Raise twenty-five.” “Call…fuck, did I say call?” “Unfortunately.” “Let me bet once more? No limit?” “Long as I can cover it.” “Hundred?” “Covered. Call.” They could have been brothers, which is obviously not true. But if they were, Drake, who was older, would have been the older of the two. Donnie moved to deal the seventh card, Drake held up a halting hand, and Donnie set the deck on the table. “Back and forth, back and forth. Inutile. Futile. I hate and I love it. Repetition, I mean. I have an…what is it, Doll, ambiguous?” “Ambivalent.” “I have an ambivalent relationship with repetition, redundancy. Listen, kid. Whud you say your name was?” “Is.” “Is?” “It’s redundant. Same again and again.” “Then say it three times so I can remember it.” “Donnie.” “Fine. I’ll do it. Listen, Donnie Donnie Donnie, I got no problem with yesterday today tomorrow, even next day, day after. I got no problem with a three second shot of a head shot over and over and over ad infinitum if only that were possible. But when clear reason is violated by again and again, I get nausea. I got nausea now. You bet like you want me to stay [Non-coitus interruptus: Both Drake and the woman on his lap in the loose mini-skirt that oft revealed as much breast as to include visions of her nipples knew that his penis, now flaccid, when erect measured virtually 7.5 inches, while Donnie’s, erect, measured just over six, which neither Drake or the woman on his lap wearing whorish skimpy yet loose undies that revealed hair tufts on demand of various wrigglings knew. In fact, of the three, none was giving any thought at all to their penises despite the fact that all were much driven by the facts of these dangling existences.] in, to stay in and keep raising, as if I were bluffing and you knew it, even though by now you must know I’m not bluffing at all. So you think you have me beat…and I respect that…I might even respect you, even though I don’t know you…But more to the point is that you don’t know me, and therefore could not possibly know how nauseating your behavior is to me; so I’m going to tell you, tell you why this kind of thing is nauseating, and how despite the fact that such is rather cliché it has to do with an incident in my childhood, an instance involving my father, the kind of thing I would hope you have in your history—not that I wish you ill, just to say I believe it’s cliché because it is universal, a fact of human nature, human and only human, though in this instance you could, and you would be right to, call it inhuman or not humane. Even if, yes it is actually, common—in its way—unique as it may be. Repetition. I repeat an old story, a story about repetition. Oh yes, it is, you will tell me it is, perverse. A boy, young, a young boy, maybe five years old, catches his first frog, I caught my first frog. And I had to have it, right? Leopard frog. We were up at Big Bear, not so far, a weekend trip from L.A. or wherever we lived around thereabouts. And I caught a frog, leopard frog, put it in my pocket, kept it with me when we went into the cabin to eat, and I forgot about it long enough, a few seconds really, because I was thinking about it, intensely. It hopped, it squeezed out of my pocket and then I snapped back to it, but then it hopped onto the table and my old man, a rough customer you might say, was about to bring a metal spoon down on it and I screamed—screamed—NO! And he caught it and there was a scene, me crying and him trying to get past my ma to fling it out the door, and jokes about eating its legs: not that it was a bullfrog, as I said, though leopard frogs can get big enough, and anyway if enough were cooked…So you see right where this is going. I get to keep it, and the next day I find a large box and perfect the technique of catching them—usually in the water, if not facing them and getting them after they angle on the hop away, confused. But usually in the water, jumping in and making back for the bank, and before anyone knew it I must have had fifty and one equals fifty in the mind of a little boy and I cried again when the old man said no, I couldn’t keep them all. And here’s the cruel part: he knows how the story will go, all of it from saying eventually yes to what I’m getting at, this problem with repetition. You know the line: fine, but you have to take care of them. We have to buy an aqua-terrarium and you have to catch insects, just grasshoppers will probably do, you have to feed them, you have to take responsibility for them. I’ll say yes, Mandrake, but they are now your responsibility. Well it’s southern California so we all play baseball, and in fact I’m not a bad player, and the old man was already teaching me, playing catch with me every day when he wasn’t gone and instructing me to throw against the cinder block backyard wall when he was. Meaning there was a quality Louisville Slugger in the house, probably half a dozen of them. [Brain trash Daddy splash lightning flash money stash jet crash civilian ash brain trash] But I bring that up, the baseball bat, prematurely, but by no means randomly, the fat of the bat, because you know, you know I am not going to walk a half hour to a vacant lot and catch grasshoppers every week. I did though, I really did, at least twice. And when you consider that by the time the old man brought the frogs up again, literally, they were down in the basement when he brought them up, I had forgotten they existed, so in fact I took quite good care of them while they were in my orbit so to speak. He set the thing right on the kitchen table and the situation was bad, couldn’t have been any worse coming upon Auschwitz, being that the dead weren’t what you’d see. Though one was dead. He held it about an inch from my nose and said see Mandrake, that’s what they’d all be like if I left you responsible. That’s why parents say no. Now I’m going to tell you why we say yes. If memory serves me right he already had the baseball bat in his hand and he cradled the, to me at the time, giant terrarium with his other arm, said, follow me, and led the way out the screen door to the back yard. He sets the thing on the ground, steps back a couple paces, bat on the shoulder, and says throw me that dead one here. Now I’m confused. I mean it’s clear he means pitch it, toss it so’s he can swing at it. But where is the dead one? I never saw him put it back in. Maybe only a second went by, then he goes, Oh, wait a minute, I got it right here. And he pulls it from his pocket, a frog about the size of my hand at the time. He tosses it and splat!, over the back fence. Now I’m relieved. We got that over with. Now I just have to go catch grasshoppers, right? Wrong. A kid your age, you see Drake, a kid your age could end up being anything. As you know my first choice is for you is baseball pitcher. And you’re off to a good start. Another is, let’s say zookeeper. Not off to a good start. But you could still be one. But right here in the here and now we need to make the best of a bad situation, which I think calls for encouraging your strength, which is, as I suggested, pitching. Okay, I’m your batter. Reach in and get me a live frog. It’s harder to hit a moving pitch—I like the challenge. I was frozen, wide-eyed. I’ll tell you again and you will obey or you will eat the next frog out of that death chamber. I got it. Now I really got it. I reached in, grabbed one by the leg, tossed it a bit low, and the old man golfed the fucker way high and out of the yard into the kitty-corner yard, probably to their door step. You learn a lot about life from shit like that: it was gorgeous, of course, prodigious, and the horror quite specifically manifest in the way the frog stiffened in death even before it reached its apex. You could actually see that. Went stiff, kept the same arc it started on but sort of…you know, like cartwheeling almost. I think I remember hearing it hit, which meant the cement stoop outside the neighbor’s door. I can’t say what state I was in at this point, but then the old man called for another, and then I knew, I knew him, and I knew we were going to go through the whole fucking squadron. And we did. And I was careful to pitch them all within range of his bat, one after the other, frog after frog, splat after splat. Can you begin to imagine how long that took if it was really fifty frogs, which is quite close to what it was. He took his time, watching each and every one to the end, the shrugging of his shoulders, adjusting his stance,

3 THE HAND MADE VISIBLE Donnie [Hole cards: 5 of diamonds, 5 of clubs] 10 of spades Drake [Hole cards: ace of diamonds, king of diamonds] 6 of diamonds Others, high card showing: ace of spades. Bet: $15$. Called all around. Next card: Donnie: 5 of spades Drake: king of clubs Others, high hand showing: ace of spades, ace of clubs, six of spades Bets: $15$ called by Drake, raised $5$ by Donnie, called by double aces and Drake, three others dropped. Fifth card: Donnie: king of spades Drake : ace of hearts Big hand: 7 of hearts Bh bets: $15$, Donnie raises after Drake calls, Bh tosses in five, a look on his face as if yet again, yet again, a hedgehog dashed across the table without upsetting the peanuts the three who dropped are fracking at, their hands coon hands. Sixth card: Donnie: 5 of hearts Drake: 10 of diamonds Bh: “Deuce, fucking deuce! Deuce of shit, deuce of my fucking asshole, deuce of the fucking Margrave of Malzovia, deuces of the long knives. Deuce deuce and deuce fucking attorneys at law. Deuces don’t even have a suit, deuces don’t fucking, deuces fucking, deuces are my balls, this fucking hand is a fucking scrotum…fuck it, I’m out.” “Guess it’s my bet. Fifteen. You raise five…Enough of that shit. We start with $25$.” “Raise five.” “Fuck?” “Fuck? Raise five?” “Raise five.” “Raise…Fuck you: raise twenty-five.” “Twenty limit.” “Right, forgot. Twe-” “Sallright: twenty-five and five.” “Okay, so what’s the limit now, smartasss? Who let this fuck in the game?” “You did.” “I know. Fine. Twenty-five limit. So there goes another trust fund. No fucking transmission of disease. They call it a disease, but ask anybody at this table, you rather have gonorrhea or an empty bank account…Twenty-five.” “Raise five.” “Fuck you: twenty-five.” “Raise five.” “Twenty-five.” “Raise twenty-five.” “Call…fuck, did I say call?” “Unfortunately.” “Let me bet once more? No limit?” “Long as I can cover it.” “Hundred?” “Covered. Call.” They could have been brothers, which is obviously not true. But if they were, Drake, who was older, would have been the older of the two. Donnie moved to deal the seventh card, Drake held up a halting hand, and Donnie set the deck on the table. “Back and forth, back and forth. Inutile. Futile. I hate and I love it. Repetition, I mean. I have an…what is it, Doll, ambiguous?” “Ambivalent.” “I have an ambivalent relationship with repetition, redundancy. Listen, kid. Whud you say your name was?” “Is.” “Is?” “It’s redundant. Same again and again.” “Then say it three times so I can remember it.” “Donnie.” “Fine. I’ll do it. Listen, Donnie Donnie Donnie, I got no problem with yesterday today tomorrow, even next day, day after. I got no problem with a three second shot of a head shot over and over and over ad infinitum if only that were possible. But when clear reason is violated by again and again, I get nausea. I got nausea now. You bet like you want me to stay [Non-coitus interruptus: Both Drake and the woman on his lap in the loose mini-skirt that oft revealed as much breast as to include visions of her nipples knew that his penis, now flaccid, when erect measured virtually 7.5 inches, while Donnie’s, erect, measured just over six, which neither Drake or the woman on his lap wearing whorish skimpy yet loose undies that revealed hair tufts on demand of various wrigglings knew. In fact, of the three, none was giving any thought at all to their penises despite the fact that all were much driven by the facts of these dangling existences.] in, to stay in and keep raising, as if I were bluffing and you knew it, even though by now you must know I’m not bluffing at all. So you think you have me beat…and I respect that…I might even respect you, even though I don’t know you…But more to the point is that you don’t know me, and therefore could not possibly know how nauseating your behavior is to me; so I’m going to tell you, tell you why this kind of thing is nauseating, and how despite the fact that such is rather cliché it has to do with an incident in my childhood, an instance involving my father, the kind of thing I would hope you have in your history—not that I wish you ill, just to say I believe it’s cliché because it is universal, a fact of human nature, human and only human, though in this instance you could, and you would be right to, call it inhuman or not humane. Even if, yes it is actually, common—in its way—unique as it may be. Repetition. I repeat an old story, a story about repetition. Oh yes, it is, you will tell me it is, perverse. A boy, young, a young boy, maybe five years old, catches his first frog, I caught my first frog. And I had to have it, right? Leopard frog. We were up at Big Bear, not so far, a weekend trip from L.A. or wherever we lived around thereabouts. And I caught a frog, leopard frog, put it in my pocket, kept it with me when we went into the cabin to eat, and I forgot about it long enough, a few seconds really, because I was thinking about it, intensely. It hopped, it squeezed out of my pocket and then I snapped back to it, but then it hopped onto the table and my old man, a rough customer you might say, was about to bring a metal spoon down on it and I screamed—screamed—NO! And he caught it and there was a scene, me crying and him trying to get past my ma to fling it out the door, and jokes about eating its legs: not that it was a bullfrog, as I said, though leopard frogs can get big enough, and anyway if enough were cooked…So you see right where this is going. I get to keep it, and the next day I find a large box and perfect the technique of catching them—usually in the water, if not facing them and getting them after they angle on the hop away, confused. But usually in the water, jumping in and making back for the bank, and before anyone knew it I must have had fifty and one equals fifty in the mind of a little boy and I cried again when the old man said no, I couldn’t keep them all. And here’s the cruel part: he knows how the story will go, all of it from saying eventually yes to what I’m getting at, this problem with repetition. You know the line: fine, but you have to take care of them. We have to buy an aqua-terrarium and you have to catch insects, just grasshoppers will probably do, you have to feed them, you have to take responsibility for them. I’ll say yes, Mandrake, but they are now your responsibility. Well it’s southern California so we all play baseball, and in fact I’m not a bad player, and the old man was already teaching me, playing catch with me every day when he wasn’t gone and instructing me to throw against the cinder block backyard wall when he was. Meaning there was a quality Louisville Slugger in the house, probably half a dozen of them. [Brain trash Daddy splash lightning flash money stash jet crash civilian ash brain trash] But I bring that up, the baseball bat, prematurely, but by no means randomly, the fat of the bat, because you know, you know I am not going to walk a half hour to a vacant lot and catch grasshoppers every week. I did though, I really did, at least twice. And when you consider that by the time the old man brought the frogs up again, literally, they were down in the basement when he brought them up, I had forgotten they existed, so in fact I took quite good care of them while they were in my orbit so to speak. He set the thing right on the kitchen table and the situation was bad, couldn’t have been any worse coming upon Auschwitz, being that the dead weren’t what you’d see. Though one was dead. He held it about an inch from my nose and said see Mandrake, that’s what they’d all be like if I left you responsible. That’s why parents say no. Now I’m going to tell you why we say yes. If memory serves me right he already had the baseball bat in his hand and he cradled the, to me at the time, giant terrarium with his other arm, said, follow me, and led the way out the screen door to the back yard. He sets the thing on the ground, steps back a couple paces, bat on the shoulder, and says throw me that dead one here. Now I’m confused. I mean it’s clear he means pitch it, toss it so’s he can swing at it. But where is the dead one? I never saw him put it back in. Maybe only a second went by, then he goes, Oh, wait a minute, I got it right here. And he pulls it from his pocket, a frog about the size of my hand at the time. He tosses it and splat!, over the back fence. Now I’m relieved. We got that over with. Now I just have to go catch grasshoppers, right? Wrong. A kid your age, you see Drake, a kid your age could end up being anything. As you know my first choice is for you is baseball pitcher. And you’re off to a good start. Another is, let’s say zookeeper. Not off to a good start. But you could still be one. But right here in the here and now we need to make the best of a bad situation, which I think calls for encouraging your strength, which is, as I suggested, pitching. Okay, I’m your batter. Reach in and get me a live frog. It’s harder to hit a moving pitch—I like the challenge. I was frozen, wide-eyed. I’ll tell you again and you will obey or you will eat the next frog out of that death chamber. I got it. Now I really got it. I reached in, grabbed one by the leg, tossed it a bit low, and the old man golfed the fucker way high and out of the yard into the kitty-corner yard, probably to their door step. You learn a lot about life from shit like that: it was gorgeous, of course, prodigious, and the horror quite specifically manifest in the way the frog stiffened in death even before it reached its apex. You could actually see that. Went stiff, kept the same arc it started on but sort of…you know, like cartwheeling almost. I think I remember hearing it hit, which meant the cement stoop outside the neighbor’s door. I can’t say what state I was in at this point, but then the old man called for another, and then I knew, I knew him, and I knew we were going to go through the whole fucking squadron. And we did. And I was careful to pitch them all within range of his bat, one after the other, frog after frog, splat after splat. Can you begin to imagine how long that took if it was really fifty frogs, which is quite close to what it was. He took his time, watching each and every one to the end, the shrugging of his shoulders, adjusting his stance,

like a real batter preparing for the next pitch. I’d have to say an average of half a minute per frog, which means more than twenty-five minutes, because they weren’t all home runs. A few, a very few, were grounders or short low liners. A grounder he’d walk up to it, move it with his toe. Watch its state of death. One especially vicious liner hit near the top of the back wall and stuck, just stuck, but it was one of the bigger ones and had some lure for gravity, and it was maybe five or ten seconds before slowly, smearing like a paintbrush, swathing down. And of course there was gore, I remember the waves of simultaneous thought: a string of guts or something stuck to the old man’s nose and fuck if I didn’t know it would have been funny under different circumstances but currently was not, yet I was afraid that even though I didn’t feel the least like laughing. At some point, of course I wanted to cry, but he warned me that if I did I would eat the rest of the frogs. It was easy not to cry, for despite the slaughter and the never-ending nature of the event, I knew something of relatively rare significance was occurring. I don’t remember getting blood or guts on me, but as we got near the end the bat was smeared, his face was smeared—though his expression was unchanged, he didn’t get all demonic like you might think people do when they work through a situation with blood on their faces and aren’t about to wipe it off because they aren’t done with whatever it is they’re up to. So it went. On and on. Until the last frog. And this is where divine fatherhood comes in. He couldn’t have done it better. The last one was smaller than average, and he really ripped into it, and we both watched and saw nothing and realized at the same time that the fucking thing stuck—stuck!—to the bat. Would ya look at that, he said in wonderment, and he started laughing, showing it to me, the flattened frog stuck splayed to the bat belly outward, and I started to laugh. And he said, I’m glad you think that’s funny, son, because otherwise you might have to think about how it was your irresponsibility that lead to the suffering and eventual death of all these live beings. He dropped the bat, said, clean up the yard, and went inside and it was never spoken of again.” A silence grew like an embarrassment of an appendage from Drake’s story, bristling with sharp hairs, and bubbling with warts, until Donnie spoke. “You want me to tell you about my pappy or should we get on with the hand?” “Well, I couldn’t help but notice you were taking notes…” “Nothing important.” “No, if you have something to say or ask…” “All right. I liked ‘swathy’, couldn’t think of a better word there.” “Thanks.” “But I couldn’t help but wonder about your father’s dialogue. You seem to have it down too pat.” “Probably a combination of telling the story fifty times and living with him for seventeen years.” “Oh. I thought you would fall back on it being the truth.” “Maybe even word for word. He did take on a simple role.” “Right” “Anything else?” “Just the cards.” Donnie dealt: Drake: king of hearts Donnie: ten of clubs “All right, kid. I think we’ve established that we aren’t going to stand for anymore of this raise five shit. How much you got left?” Donnie pulled a twenty, a ten, a five, and two ones from his right front pants pocket. His wallet, they both knew, was empty. “37.” “Here’s the deal. I hate sons a bitches who buy hands. I got plenty more than that left and it is my right to bet it—“ “But Drake, didn’t we—“ “Shut up. What he was going to say is didn’t we put a hundred limit on the game. Well that was before you turned up, so I figure it doesn’t bind you or myself as related to you, leaving us with a nebulous circumstance. And normally, what with all the money in the pot, I would just bet what you have; but, see, I really fucking hate people trying to buy the pot, which is what you’ve been doing. You’ve obviously played before, know what you’re doing, been winning pretty much since you sat down. But you took it a step too far. You’ve been getting good enough cards, maybe one hand you can just fold with the crap you’re dealt. But no, with our losings, you try to bulldoze us right off the table with my least favorite bluff—I call it the accumulator. You have such a great fucking hand you want to keep us in with restrained raises. We know you got a great hand. Psychologically you got us by the nuts—we’ve been losing so regular to you that our first instinct is flight when you bet and raise. You got two aces up off and running—got him thinking even three aces can’t beat you. Raise five, raise five, raise—“ “Why don’t you cut the shit and make your bet. If you want to buy the pot buy it. I’m just a first year student in a university spending a Friday night.” “You got money in the bank?” “Probably less than most.” “You got a card, a bank card?” Donnie kept quiet. “What if I ease off a bit and just bet five hundred?” “Call.” “We go get the money now?” “I’m not leaving this room until the hand is settled.” “You swear you can cover it?” “I can cover it.” Drake stood, pressing the woman to him so she wouldn’t topple before getting her hooves right on the floor, walked to an enormous oaken desk, opened a drawer, pulled out a wad of hundreds, and peeled off five. Sitting back down, he gestured for the woman to restore herself in her place. “No need to get dramatic. Pot’s light five hundred, to be collected immediately after the cards are shown.” “Unless I win.” “You want to raise?” “Couldn’t stand another childhood story.” “Fine.” Drake turned up his full house, looking straight at Donnie’s face. Donnie looked down at the table, where he turned over his four fives. The pot was about a thousand more than what Donnie had put into it.

like a real batter preparing for the next pitch. I’d have to say an average of half a minute per frog, which means more than twenty-five minutes, because they weren’t all home runs. A few, a very few, were grounders or short low liners. A grounder he’d walk up to it, move it with his toe. Watch its state of death. One especially vicious liner hit near the top of the back wall and stuck, just stuck, but it was one of the bigger ones and had some lure for gravity, and it was maybe five or ten seconds before slowly, smearing like a paintbrush, swathing down. And of course there was gore, I remember the waves of simultaneous thought: a string of guts or something stuck to the old man’s nose and fuck if I didn’t know it would have been funny under different circumstances but currently was not, yet I was afraid that even though I didn’t feel the least like laughing. At some point, of course I wanted to cry, but he warned me that if I did I would eat the rest of the frogs. It was easy not to cry, for despite the slaughter and the never-ending nature of the event, I knew something of relatively rare significance was occurring. I don’t remember getting blood or guts on me, but as we got near the end the bat was smeared, his face was smeared—though his expression was unchanged, he didn’t get all demonic like you might think people do when they work through a situation with blood on their faces and aren’t about to wipe it off because they aren’t done with whatever it is they’re up to. So it went. On and on. Until the last frog. And this is where divine fatherhood comes in. He couldn’t have done it better. The last one was smaller than average, and he really ripped into it, and we both watched and saw nothing and realized at the same time that the fucking thing stuck—stuck!—to the bat. Would ya look at that, he said in wonderment, and he started laughing, showing it to me, the flattened frog stuck splayed to the bat belly outward, and I started to laugh. And he said, I’m glad you think that’s funny, son, because otherwise you might have to think about how it was your irresponsibility that lead to the suffering and eventual death of all these live beings. He dropped the bat, said, clean up the yard, and went inside and it was never spoken of again.” A silence grew like an embarrassment of an appendage from Drake’s story, bristling with sharp hairs, and bubbling with warts, until Donnie spoke. “You want me to tell you about my pappy or should we get on with the hand?” “Well, I couldn’t help but notice you were taking notes…” “Nothing important.” “No, if you have something to say or ask…” “All right. I liked ‘swathy’, couldn’t think of a better word there.” “Thanks.” “But I couldn’t help but wonder about your father’s dialogue. You seem to have it down too pat.” “Probably a combination of telling the story fifty times and living with him for seventeen years.” “Oh. I thought you would fall back on it being the truth.” “Maybe even word for word. He did take on a simple role.” “Right” “Anything else?” “Just the cards.” Donnie dealt: Drake: king of hearts Donnie: ten of clubs “All right, kid. I think we’ve established that we aren’t going to stand for anymore of this raise five shit. How much you got left?” Donnie pulled a twenty, a ten, a five, and two ones from his right front pants pocket. His wallet, they both knew, was empty. “37.” “Here’s the deal. I hate sons a bitches who buy hands. I got plenty more than that left and it is my right to bet it—“ “But Drake, didn’t we—“ “Shut up. What he was going to say is didn’t we put a hundred limit on the game. Well that was before you turned up, so I figure it doesn’t bind you or myself as related to you, leaving us with a nebulous circumstance. And normally, what with all the money in the pot, I would just bet what you have; but, see, I really fucking hate people trying to buy the pot, which is what you’ve been doing. You’ve obviously played before, know what you’re doing, been winning pretty much since you sat down. But you took it a step too far. You’ve been getting good enough cards, maybe one hand you can just fold with the crap you’re dealt. But no, with our losings, you try to bulldoze us right off the table with my least favorite bluff—I call it the accumulator. You have such a great fucking hand you want to keep us in with restrained raises. We know you got a great hand. Psychologically you got us by the nuts—we’ve been losing so regular to you that our first instinct is flight when you bet and raise. You got two aces up off and running—got him thinking even three aces can’t beat you. Raise five, raise five, raise—“ “Why don’t you cut the shit and make your bet. If you want to buy the pot buy it. I’m just a first year student in a university spending a Friday night.” “You got money in the bank?” “Probably less than most.” “You got a card, a bank card?” Donnie kept quiet. “What if I ease off a bit and just bet five hundred?” “Call.” “We go get the money now?” “I’m not leaving this room until the hand is settled.” “You swear you can cover it?” “I can cover it.” Drake stood, pressing the woman to him so she wouldn’t topple before getting her hooves right on the floor, walked to an enormous oaken desk, opened a drawer, pulled out a wad of hundreds, and peeled off five. Sitting back down, he gestured for the woman to restore herself in her place. “No need to get dramatic. Pot’s light five hundred, to be collected immediately after the cards are shown.” “Unless I win.” “You want to raise?” “Couldn’t stand another childhood story.” “Fine.” Drake turned up his full house, looking straight at Donnie’s face. Donnie looked down at the table, where he turned over his four fives. The pot was about a thousand more than what Donnie had put into it.

(Author’s note: For those who don’t know poker, to put it simply the best five cards of one player are up against the best five of the others. In this game, Drake believed Donnie had five spades, three up and two hidden. He has two kings and two aces and hopes his last card will be one or the other. If he gets one of them, he will have three of one, two of the other, which is a full house and beats five spades, a flush. In fact, he was so sure of his analysis of the hand as it played out, he missed the possibility that Donnie might have four cards of one kind, which beats a full house. Donnie does have four fives, two right away that are hidden, and two that come up quietly as Drake looks for spades. So by the sixth card Donnie knows he has won.)

4 OLD EPHRAIM

The mechanism that relayed the visual majesty of a still panorama of mountain and valley, river and tree line, snow and sun, shadows unseen yet known and darkness invisible where life ate life and thought not, or where desert yielded scrub cactus and range, the living seen still or as the disappearance following on rapid bursts of movement, what relayed these for indescribable sensory bloom inside a man as majesty, this is what Tom Garvin sought with his meditations and was awarded for delineating fecklessly in prose poems.

Garvin’s specific and private precocity had always been intuiting and then knowing absolutely from his age of reason onwards that no single thought he managed to stitch independently was original to himself. His misfortune was that this awareness defeated all ability to derive pleasure from anything he wrote or material benefit from what he wrote that won him praise and easy employment. He wondered whether this insight or curse somehow was passed down to him as knowing an ancient landscape that relentlessly imposed its brute determinism on men, and knew that only bones remained of the others who had wondered the same.

Garvin knew and could never know that such a still, majestic landscape, witnessed by eagle, falcon, buzzard, hawk, and owl with like indifference removed by distance of time the sight of Old Ephraim near the Salmon river in what Garvin would know as south-western Idaho awakening in early April back when mountain men outnumbered the traders they enriched, surviving in large part by knowing the natives and learning their techniques for survival, oblivious of the cataclysm they introduced and therefore largely under the delusion that they, also, were natives and so what came after was accretion of betrayal.

In some ways bears are like people; for instance, when they awaken some do so with a spark to immediate clarity of mind and sense, energy and high spirits, while others stumble about groggy for varying gropes of time. Old Ephraim, this particular Old Ephraim, was among the latter. In mid-April he woke, lay still for some hours before, moved by instinct, he rolled from his crevasse where the curve of erosion met the sharp of tectonic thrust onto the open verandah of the horizontal rock ledge, rolled further before his mind could strain for consequential thought, fell fifteen feet to a slope and rolled, tearing through saplings where a few years before a fire had briefly blown in geometrical spectacle burning a line of trees near where the slant of earth gave way to more monumental stone. His tumble was not unlike that of a funnel cloud’s in its distinct resultant path to where he slowed and finally thudded against the trunk of a stout, high pine with yet enough force to bring heaps of snow down upon his head and the ground around. And there he sat and remained sitting—one could easily imagine him pulling a bottle of whiskey from a pocket in his dense coat with the muted glee of a boozer upon yet further survival of dumb luck. He had yet to feel hunger, and what pain from scratches and the concuss caused by the impact against the tree he was oblivious to. In fact, come late September he might choose to hibernate in the same crevasse should he find himself still in the area for all the comedy mattered to him.

If nothing else, it can be assumed that in the attenuate coming to senses his hunger was a relief if compared to the frenzy of the previous year’s berry barren Autumn hyperphagia. More than likely the hunger grew in stride with his mind, for he remained seated, back against the tree, to nap several hours, waking again to find night had blackened the scarcely recalled day. So he sat against the tree like a tavern regular undisturbed at his bar stool hearing or not a soft humane Let yourself out, Cyrus. Thus Old Ephraim slowly rose barely ahead of the pace of the sun, instinct stumbling him generally downward and toward water.

The biological and zoological sciences have yet to yield definitive conclusions regarding the legendary poor eyesight of bears after decades of study, daring but to aver that they probably see somewhat better than was previously thought. This is probably true, the previous native wisdom having been derived from the particular indifference displayed by large, sated predators. Bears are not much concerned with activities of live creatures within their near vicinities (I refrain here from discussing mother bear and her cubs) when hunger is not at issue—in fact, it is not uncommon for a tired bear to drop to his side and sleep at will, day or night, on trail, in grass tall or short, in woods or on the plain.

By the time Old Ephraim’s senses had focused on food he had arrived to the bank of the middle fork of the Salmon river between the confluence with Big Creek and the Salmon itself. The water was Spring high overflowing grassy banks, a good place for stranded fish to flop in flounder in blind-like effort to re-immerse. So Old Ephraim slow-loped the riverine for two or three miles, the focus and modest effort inducing a more live quotidian hunger by the time he reached a slow narrow feeder stream, barely fifteen feet across and so shallow that rock rose humped high and dry and jagged and dry. Here at this confluence, Old Ephraim stood erect on his hind feet, stretching slowly to his full height of almost precisely thirteen feet from pawsole to furred headcrown. Herenow the sun lit his fur, the color of dry wheat, but for a split stripe of black, a band down the center from head to something like a waist, where it spread like the wings of a mythic bird to blacken his ass and haunches. Old Ephraim’s territory was harsh to mankind and thus he had been spied by human eyes but oncet, just a few miles from where he now stood, nearer the Salmon, by a lucky mountain man name of Jenkins*, who spread the too oft disbelieved for legend word of the bear he called Old Black Ass from camp to camp, trading post to trading post: ‘I’s a maybe a unner foot up hills down air win en I took me a good long gander to pooter in me skulls afor I sneak away like air bobbercat quiet so to memmer nere come backen this are win two hunner mile.’ Only the size he claimed for Old Ephraim was subject to disbelief, and when called for by whiskey mockery, for Jenkins rightly ‘reckoner be thirteen foot ifn she stand, wich I yen no cline to wait fer.’ The listener was rare who had not seen a large grizzly himself, say an eight to ten footer standing, so Jenkins was simply categorized a tall tale teller and generally let be to speak.

As he stood looking down, Old Ephraim saw the vague outline or the perfect detail of a two foot fish flange off from the river into the calm of the stream and begin a slow advance, as if in the relief of an unanticipated safety evident upstream. The bear followed, first along similarly grassy banks, but soon enough into the waterwind through forest, until the stream had narrowed to a bare nine feet, where at a sharp bend the water both raced and pooled, the pool a still depth aloof the rush of stream. And precisely here Old Ephraim found his feast of fish: trout, salmon, carp, cat, and, to begin with, the fish he had followed, stabbing the shovel-nosed sturgeon as it hesitated between stones, fins out flanked to either side, wherefrom it was veritably torn from life, impaled by scimitars of bone, the claws raking in sudden strike, fierce as the surreal thrust of a viper, the fish to his maw before Jenkins could have dropped his jaw had he been there.

Had he been there, Jenkins would have learned a thing or two about the food chain. For Old Ephraim, having found something like a perpetual food source, remained within about 100 yards of his feed pool. There were berries, wild strawberries, cherries, something like an apple tree even, but these would be bearing beginning in July. For now it was a bounty of fish, water and, as it so happened, no niggling parasites. Two otters regularly balleted in the stream, sometimes making a meal of the smaller fish in the pool, as did raccoons, a large family of them, sometimes as many as seventeen moving in a good few hours after Old Ephraim moved off. Other animals–deer, elk, skunk, muskrat, even an odd pod of buffalo–dropped by or passed on or both, but no movement outside of his own did Old Ephraim intake with interest. An observation of his life those days would make a man ponder on the nature of human pursuit, for if that ain’t what’s called living, nothing so pleasing has grace of life; but one would be remiss not to think on Old Ephraim’s satisfaction, physically evident yet as part of the natural scene itself perhaps not of access to the slanted rays of morning sun on the rippling stream, the gliding loops of the otters in the aflow, the delicacy of a raccoon’s dining upon a trout, holding the flopper astab yet no more hurried in his repast than a vulture at yon morning’s slaughterfield. What indeed did Ephraim make of the geometries of scarp, tree and endless space, asymmetries of slope, boulder, forest, illusion of order, illusion of nothingness, illusion of eternal content?

The cynic surely would grant this state paradisiacal, for soon its fall was arranged, born on an imprecise wind that didn’t so much as rustle the leaves of the tree under which Old Ephraim had just awoken. A turbid odor, a death odor, a new odor, rank hide, matted unembodied fur, unnatural—chemical—emanations, aswirl in a scarce wind, katabatic, live and bare as a raven-picked bone, an ant-swarmed bone, dry and pregnant with intrusion; he looked over his shoulder, sniffed, his swollen damp nostrils contracting and expanding like valves freshly torn from within a body in a blind seek. Noises compounded: a rain drop and more drops, and then rain, but a foot step and then more footsteps, and the harsh physicality of human voices, a phenomenon without rhythm or sense. Old Ephraim was fifty yards up hill from the stream that the three men were walking astride.

Not hide nor hare:

Ripen and rot ripen and rot these two feet are all you got n if uncle bob were here I curse your unborn may they be rabid badgers nibbling your rotting edges fierce fitzpacker ripen and rot uncle bob and circulatory issues one dead doctor and that joke those jokes I got circulatory issues he says and I says tell me what’s really wrong with me and he gets nervy and high talkin and circulatory issues you don’t like it and I interrupt and says circulatory issues are them what keeps moving around so you can’t ketch em and I said your telling me get a second opinion, well I’ll tell you what to say, I said doctor give me a second opinion, and here he gets nasty and I took him by the throat and said when I ask you one last time fer a second opinion you say, all right you smell bad too, and I shakes him til he says all right you smell bad too and I put a stop to his issues of circulation by squeezing his throat to the cy-cumfrance of racoon’s pinkie, ripen rot stop not, foot rot til one day fitzpacker gets a snoot full a uncle bob who shoulda comed with me but some folk got their furrows dug and uncle bob had the two rivers said maybe we meet if ye takes the overland back er a whale boat puts to in norlins whin I’s there, not that he figgered my idea fer a dead muskrat, no, he liked it, said I was the only smartn in the fambly though I think it took only the sense of thinkin alone, cause ya got yer couple a rich and million poor and why, cause of failure but ifn you could make failure succeed you could be a failure and a rich man or at least get yerself in clean clothes on a bit a land lightning clarity claires kinby, o but I see I know in the ripenenrot a blandness will erupt or the Earth like an tempted sunrise and all white peeples ill long fer nation-states and fierce, bibly no meanin battles which in millions rush headlong to their sudden, caint be splained and terrfying deaths o fuck I’m not right in the head no more…no more of the ripe, the rot, the whatnot shitplot I summon Uncle Robert Robitaille from his bungboat polacre Missouri misry through my fancy fungals O Robert deliver me from this Fitzpacker most foul fartsack smite—

THWACK! Fracked the fist of Fitzpacker backhand fast against the fraught face of Hector Robitaille (surely that’ll bring a nearby bruin to bear!).

‘Gyup, ya shatpup! Ain it yar graynmoodah gone fixn yar ets issut?’ THWAKK! ‘Gyon witya sloosecrappin bunghowsin shatpup!’, which though colorfully delivered lingo-wise was yet delivered with restraint of homicidal, for, and only for, he needed the body of the man sound enough to pull what he called a tran-sumddie, a triangular, makeshift wooden dragsled of white man make from Injun design which would soon be laden with inanimate, nay, hollow, beaver, and the soon meaning the better to be on the return through tribes of fisheaters and rootgrubbers, before the Blackfoot traipsed widely afield of winter’s hydie hide to make menace upon what white men could be captured and slaughtered, robbed and rapined, and, for the sport of it merely, what rootgrubbers and fisheaters could be caught in small defenseless groups and tortured, raped and slapped about.

Robitaille duly dressed rapidly amongst the needless funs of further gruff kicks that served only to delay the departure from the camp, observed with fatalistic remove by the third hidebound human, mountain man extraordinaire Jeffers Phoeble, who reckoned little but what he deemed of pragmatic import, such as that one or two days grueling final stomp would bring them to the cache of beaver the winter come sudden and final to force his secreting down the Salmon and two hours up an unmapped tributary and the appearance of a bear of a height greater than most pines hereabouts, standing still yet peering with what could be taken for intense interest at Fitzpacker and Robitaille from the distance of one thin and shallow stream.

Battering about Robitaille being more avocational, habitual, not to say, certainly not, needless or arbitrary, Fitzpacker’s peripherals were alert enough to take in the dark tree a mere seven feet distant registering its density of pine needle and anon the imposition of it where once it weren’t, such that in due time, time enough, he looked up to see Black Ass, taking in stomach, chest, legs, chest, head, yet failing to pause long enough to attempt deciphering the gaze of the bear, or bar, as he would later call it in the telling ad infinitum when he would bear-beat his chest to emphasize his clarity of thought as he whispered to Phoeble ‘Grab his gun’, meaning Robitaille’s, slowly now—yet forgetting his most noble original wordthoughts to the effect of ‘what doomriding banjaxery be this?’–and the bear cocked its head an inch or two leftward, away from Phoeble, who obeyed with cunning, ‘Tran-sumddie’, Fitzapcker ordering/Phoeble obeying, Robitaille by now on hands and knees looking up at the bear, taking in the bear, wondering at the bear, his physiology a husk and there a bear, ‘Nah slewly tie the foodstuffs, jist slewly take yer start in whin ah siz git we git, jist whisper git it’, ‘git it’, and quicker than a gentleman can say, ‘So seein death’s stalwart emplackabeel fetcher I kipt mah whets about me in panicky Phoebles I did calm,’ Fitzpacker lurched down to embrace Robitaille, whom he lifted over his head and flung full flight across the brook into the broadest beam of the bruin, who upon this assault reacted with simple pawscrapes to shoulder and thigh, and having become angered some, and Robitaille rolling about on the ground before him, clappering into the stream, halted said man with a scalp scraper that flipped him onto land, lunged forward and swiped again, this time slicing his throat. Even Black Ass would not recall what noises he made, but they were fearsome bear moans, for Phoeble, having a bit of the humane in him and confident of being unseen, had stopped, crept back and watched the dénouement, a word he figured the French Canadian would appreciate epitaphically, from distant cover, not creeping off to join Fitzpacker until he had seen the throat slice and final paw slicing back flipping dismissal of the man by the bear, who tossed Robitaille headwards over feet and atwist so that he came to rest upstream and head up against stream. ‘Dayed no question,’ was how he would put it.

Having vanquished his flying attacker, and being still of an inclination to devour fish rather than manmeat, Huge Ass, as one variant would later have it for the black mark extended beyond the rump in such a way as to emphasize those halves, followed, purely out of curiosity, the skittering, panicked duo a short ways, their tran-sumddie splintering to weightlessness as they clippered, until they were disappeared round a bend in the stream, the clanking clatter of their goods fading like a bird flying off and so of some degree of normalcy, whereupon he returned to his pool, clawed an eight pound trout and squatted to make his repast, likely not having forgotten the dying creature with blood gurgling and bubbling from his throat wound a mere five or six meters away on that opposite bank, his head anointed by serendipitous leaps of fresh water to bath his torn scalp, which was attached like an unglued wig to the skull within which despair was delayed by delirium, and just above which an odd, let’s say stray, branch of rootleberries hung low and nearly to the very lips of that natural wound, his mouth.

To which tale Garvin when in secure solitude would cast such thoughts as O great-great grandfather, indeed your notions were noteworthy, yet not novel, and your bravery nought but the naïve, the optimism a dupe’s, ye golden fool, your clearest longsight the mere premeditiation borrowed from a distate age, the giftrickery of others and stronger, your true knowledge of currents of air and not the rootworks upon which so long so far you trod.

Of Uncle Bob, Garvin never heard, and what know bears not the worth of a fart post-lit.

*For more on this and other characters considered herein of little merit, see the author’s forthcoming Characters of Brief Mention and Little Merit in the novel The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas

Chronologicals

I recently found copies of my first two novels, The Stupid Persistence of Inanimate Things, or, Carcass of the Known Self; and Taxi Cabaret, the Adventures of a Fat Nihilist. Both were finished in the early 90s, written by hand and typed with a typewriter. Neither has been typed into a computer yet, though the process has been started with Taxi Cabaret. Leaping ahead, I’ve just had two novels that have been translated into Slovenia published here–in Slovenia–to an austerity shadowed silence. So a sort of symmetry is established and anything further I write will shatter that illusion.