corona/samidat is a non-profit press. authors receive 50% royalties once expenses are made, the other 50% goes back into the press.

for specific ordering techniques advice and directions to the ratline, contact rick.harsch@gmail.com

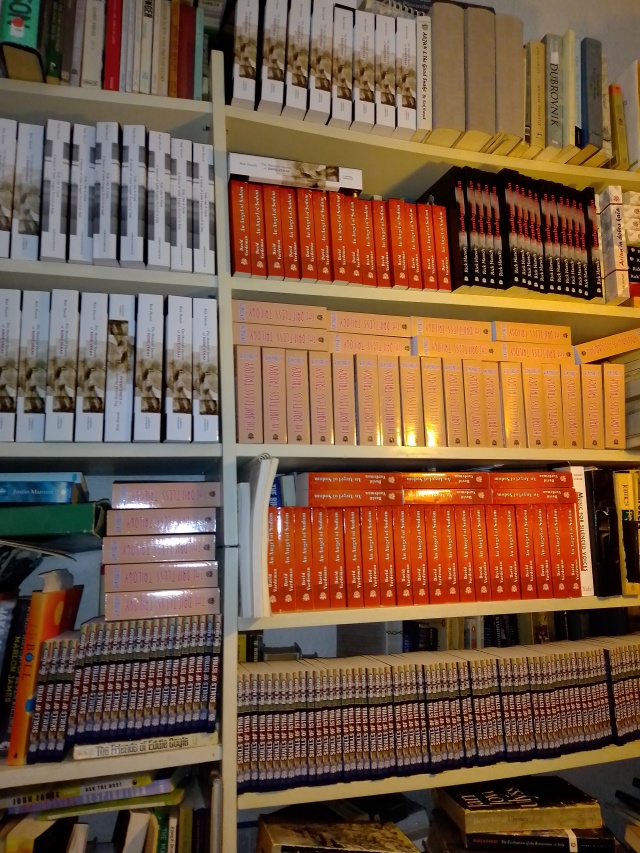

These are our magnificent printers, the Knapic family, who are from a bit east of Ljubljana but work there on Trieste Street–Tržaška cesta. They do an incredible job with the books:

By the way, in Slovene knap means miner, so I need to ask them about the origin of their name. There are a lot of mining towns on the Sava, which flows their direction if a bit south of there. If you hear a Slovene say ‘Mat kurba!’ you know they are from the Sava mining town of Trbovlje.

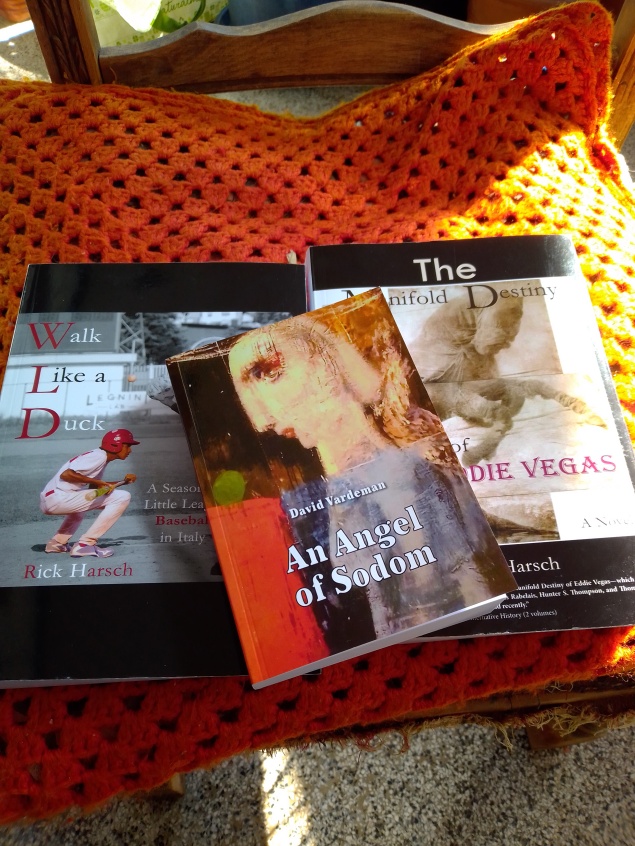

First photos of the books and basic information, then more information on the books (part II of this blog).

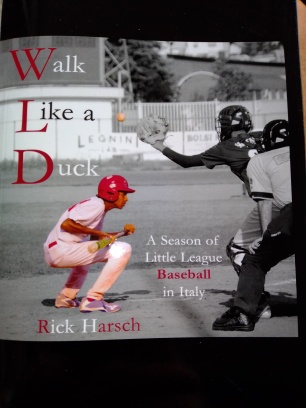

- Walk Like a Duck, a Season of Little League Baseball in Italy, by Rick Harsch, 646 pages. 20€/20$

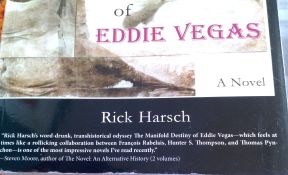

- The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas, by Rick Harsch 717 pages. 20€/20$

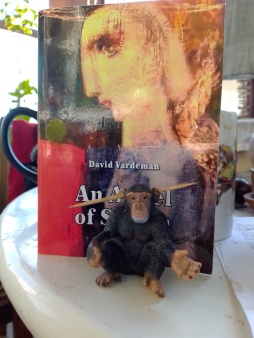

- An Angel of Sodom, pocket size (148mm X 105mm), by David Vardeman, 416 pages. 10€/10$

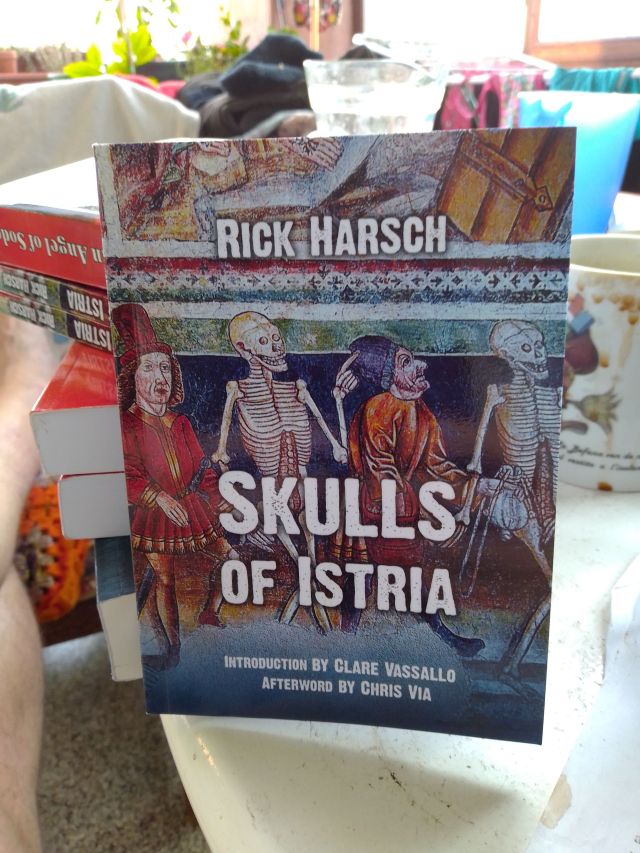

4. Skulls of Istria, by Rick Harsch, pocket size, errata slip, 175 pages. 10€/10$

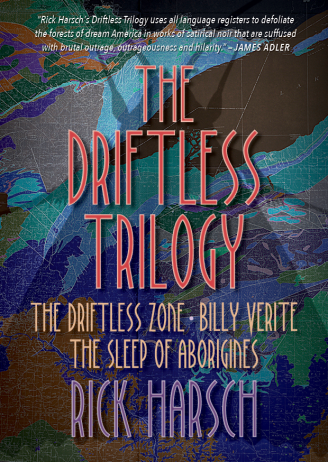

4. Skulls of Istria, by Rick Harsch, pocket size, errata slip, 175 pages. 10€/10$ 5. The Driftless Trilogy, by Rick Harsch, pocket fat size, 725 pages. 16.50€/16.50$/15.00 (€? $? Australian special.)

5. The Driftless Trilogy, by Rick Harsch, pocket fat size, 725 pages. 16.50€/16.50$/15.00 (€? $? Australian special.)

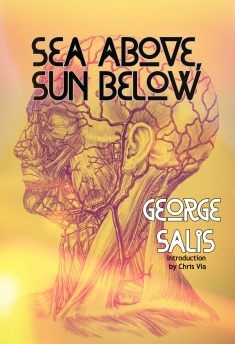

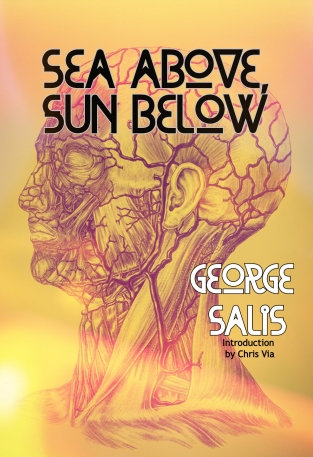

6. Sea Above, Sun Below, by George Salis, pocket size, 366 pages. 10€/10$

We haven’t finished with prices. There is the disturbing matter of postage. I have sent a bunch of books by boat, not having thought about it, simply sending them navadno (normal), and they are taking a very long time to reach their destinations. All prices I give now will be letalsko (air mail). Air generally seems to require an extra 2 euros, so you simply need to let me know if you wish me to send them by boat and subtract 2 euros from the total.

The corona aspect of this press includes the lower prices for the books. The first two were going to be sold by the press I fled from for 26 and 27 dollars. So they are now down to 20, euros for Europeans, dollars for new worlders and others have the choice. But the post is a relentless matter and I want to recoup the price (except for envelopes). So I will give you the latest euro prices and ask those who pay in dollars to convert using google euros to dollars or something like that.

Books 1 and 2 each cost 8.57€ airmail.

Skulls of Istria costs about 4.50€ airmail.

The other three cost 5.42€ airmail.

Multiple books are cheaper. For, instance, 4 copies of The Driftless Trilogy cost about 15€ the other day.

When I don’t know what the post is for a certain combination of books I am happy to accept postal payment after I know the precise charge, meaning after I have sent the books. I have made that arrangement so far with two people this weekend.

Warehousing

One of Ronald Reagan’s gifts to US and world culture was a tax on warehousing of books. corona/samidat books tax the shelves to some degree, but we pay not warehouse tax.

Here are some more photos; as I had trouble uploading them earlier, I am now in a slumberous phrenzy of fotogyration:

to be continued

continuing

corona/samizdat, an independent imprint of Amalietti&Amalietti

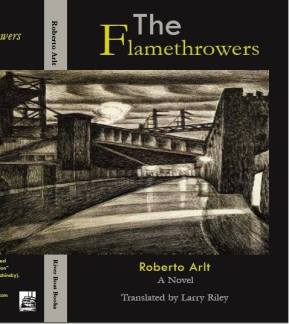

This press began under emergency conditions when I was forced to withdraw The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas from River Boat Books because an important review was going to coincide with the release of the book and the publisher of RBB, Peter Damian Bellis, tried to convince me it was fine to release the novel with only 16 advance copies ready for sale. The main faults with the advance copy were the lack of a table of contents and no blurb from Steven Moore on the front. While I don’t relish the notion of tarnishing a person’s reputation by revealing his name, when that person’s behaviour has reached a degree of the egregious that eggs me toward extreme eggitation, I find it necessary to restrain myself only at the point where you readers might tire of the topic. The fact is that not only was this the fifth publication date planned for the book, Bellis did not tell me that he was so in debt with his printer that there was no chance of printing the final version of the book for months. So on about April 16 I pulled the books, which were due out on May 26. (The story leaves Bellis behind, so thank the keyboard angels for parentheses: most pertinently, it has come to light that back in February he sold multiple phantom copies of his own out of print book, collecting the money for books and postage and simply not sending anything. Patient purchasers waited a long time before contacting him and myself and various others, trying to understand what was going on because the last thing one expects in the book world is such as the outright swindling that in fact occurred.)

I borrowed money and arranged printing of Eddie Vegas and Walk Like a Duck, a Season of Little League Baseball in Italy, here in Slovenia, and the books were available, remarkably, by April 24. And the printers are great. Over the next few weeks, I began thinking it might be a good idea to print Skull of Istria, to liberate it from the fiend as it…was. Yet when a small amount of unexpected dough came to me, a finer thought intruded: what about David Vardeman, who by this time not only wanted nothing to do with Bellis, had no idea whether Bellis, who intended to publish him, wanted anything to do with Vardeman. I would publish Vardeman! The exclamation point is the lightening strike, as opposed to the silly little bulb, of inspiration. Simultaneously, two notions were swimming about the muckponds of my mind (allow me the occasional romantic turn of phrase): how the fuck to be a publisher without really being a publisher and what a marvelous opportunity to bring back the pocket book. My former Slovene publisher, Amalietti&Amalietti, agreed to take on the imprint corona/samizdat and it turns out the pocket size books are truly pocket size and far less expensive to print than larger books. So upon the publicaton of David Vardeman’s collection An Angel of Sodom the actual corona/samizdat was born.

David Vardeman is by birth an Iowan, by nature a fricasee, an author of imperturbable visions. I am still waiting for an independent review of his book to appear. Til then, I am his greatest known fan, and I suppose it would seem a bit incestuous for me to praise his work here where I have no idea whether you are interested in an elusive blend of surreal, hyperreal, and the Beckettian banal, in a novel and stories laced with venomous and quirky surprises, psychological insight moving about on artificial limbs, folly modernized into uncontrollable higher gears, a book I could as well introduce by quoting his Mr. Perlmutter’s introduction in a boardroom “…allow me to introduce my father who today has joined us in his magnificent pig’s head.”

David Vardeman is by birth an Iowan, by nature a fricasee, an author of imperturbable visions. I am still waiting for an independent review of his book to appear. Til then, I am his greatest known fan, and I suppose it would seem a bit incestuous for me to praise his work here where I have no idea whether you are interested in an elusive blend of surreal, hyperreal, and the Beckettian banal, in a novel and stories laced with venomous and quirky surprises, psychological insight moving about on artificial limbs, folly modernized into uncontrollable higher gears, a book I could as well introduce by quoting his Mr. Perlmutter’s introduction in a boardroom “…allow me to introduce my father who today has joined us in his magnificent pig’s head.”

George Salis is what I like to call a young buck. Still in his 20s, he sent his first novel, that there book to your left, to 100 or so publishers before the shambles that is River Boat Books accepted it. So I got to know George and his very ambitious and beautiful book. George is a talented critic and interviewer, which you can witness here: https://thecollidescope.com/, where the latest accomplishments include a review of Alexander Theroux’s Laura Warholic and an interview with Theroux himself. As for this novel, I leave it to the talented and increasingly popular reviewer, who wrote the introduction to this book, Chris Via, to tell you:

While we are on Chris Via’s youtube channel, we might as well continue with his review of The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas:

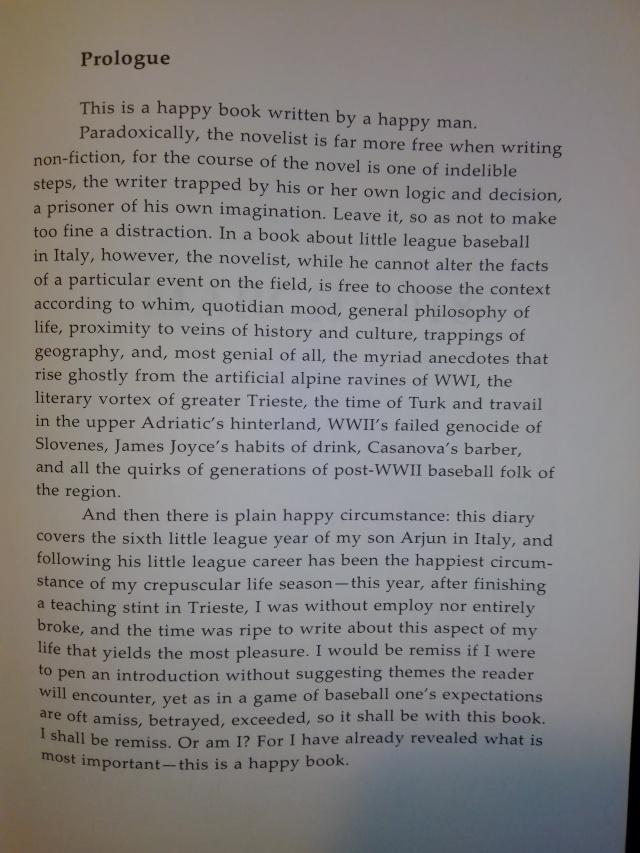

Walk Like a Duck, a Season of Little League Baseball in Italy

By design undisciplined, this diary of a baseball season is mulitidisciplinary, and if nothing more it is certainly a successful antidote to George Will, that stuffy fascist who is forgiven too much for loving baseball.

To your right is my son, Arjun, a few years before the season covered in the book…

Life Vardeman’s book, Ducks has yet to be reviewed, so I will offer a pertinent page as description:

Skulls of Istria

Peter Amalietti, the publisher of Amalietti&Amalietti came up with the brilliant idea of using a dance of death fresco painted in the 14th century in an Istrian church not far from where I live in Izola to decorate the cover of this novel. I’ll be forever grateful. This novel comes with an errata sheet, for on the very first page a line is missing. There are also spacing errors and uninvited dashes intervening. This is the result of reducing the size of the book by changing fonts and lax checking by an author who had been lulled to lazy by the previous successes of the copy feller and printers. I could not find any more actual textual errors, and in my opinion the number of the other errors is minimal–there seem very few as the book proceeds past the first chapter. It would not disturb me–and it does not–but reader beware. The book has a preface by the mysterious Stuttgartian Klaus Hauser, an introduction by the Maltese translator and literary professor Clare Vassallo, along with an afterword I will offer here by Chris Via, who, having now come up three times, I might use an excuse to discuss what I really think about the appearance of the incestuous in this cooperative literary venture. All of us involved from the United States–let Gospod Amalietti speak for himself–share the same combination of disdain for the literary establishments of particularly the US and the belief that what we do ought earn us a living. The problem is not just that the publishing industry is so warped by profit motives misperceived as needs, but also that the culture in general is insufficiently art bemused to form a phantasm of cultural need that must be granted life as a governmental fait accompli. Absent a culture worthy of human history, writers must at times find their own places, work together, help each other, and if necessary spread word about each other and their works. Here I will tell you to begin preparing yourself for George Salis’ next novel, a maximalist masterpiece still in the molding, molting your way as the novel Morphological Echoes. Hints of his genius abound in the book available now from corona/samizdat. Vardeman is older than I am, so his debut may be his rabbit song–if so, so be it: I have derived such a virtual warm rainy season of pleasure since its printing, from re-reading stories, finding new ones, simply holding it, looking at the remarkable painting on the front (detail from a painting called Angel by Edvard Belsky) and I know it will mean even more to David Vardeman himself–once it gets to the US (no more mailing by boat except by special request).

So then, another round of applause for Chris Via:

Review of Skulls of Istria

Chris Via

What begins as a confessional novel with the casual beckoning of William F. Aicher’s A Confession , Albert Camus’s The Fall , and László Krasznahorkai’s “The Last Wolf” transitions into a frenetic descent into the bitter truculence of William Gaddis’s Agapē Agape and finally into the intense crescendo of historio-geographic onslaught found in Henry Miller’s Black Spring and Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night . Yet Rick Harsch, an American expatriate living in Slovenia, stands out from the pack with an utterly original voice, a craftsman under the spell of Joyce, in command of every element of the prose. Not an ellipses is out of place.

The rambling narrator, who cares not whether his subservient audience of one is coherent or not, sweeps the reader away like the famed burja, a powerful wind that blows from the Hungarian basin to the Adriatic. From the first page we know that our narrator will be digressive, forceful, and sardonic. Who better to give us a diatribe of eastern Europeans and Slavic history? Matching the ever-rushing pace of his confession is the glut of word play, effortlessly compounding English and Slavic languages to achieve neologisms as poignant as they are inventive. A small example would be “squidnuncs,” which, in the context of fishermen, is a maritime play on the word quidnunc (an inquisitive, gosspiy person).

Effortlessly peppering the lingual rampage are an abundance of aphoristic quips and deft locutions: “Hyperborean philosophers bleating Wagnerian from the peaks”; “Never mistake religious or linguistic fidelity for the abominable integrity of blood”; “…that’s the best thing about being in a foreign land, the language barrier, it takes a great deal longer to despise the people you meet…”; “…what are academicians if not gangsters of the mind?”; “…American tourists always think that to step out of western Europe is to step into a war”; “…fascism is not possible without nationalism”; and “You don’t acquire virtue by the evil of your adversary”.

The narrator is a defrocked historian, whose credentials are stricken on the discovery of plagiarism. Nonetheless, his mind is brimming with historical knowledge, especially of the eastern European and Slavic territories. Istria is an interesting locale shared as it is between the three countries of Italy, Croatia, and Slovenia. From this store of knowledge, I was forced to dig into the stories of Josip Broz Tito and Gabriele D’Annunzio, among others. You get the sense that this narrator (and his creator) absorbs every book and every conversation on these matters. He mixes facts with the jousts of many presumably late-night conversations over maybe a little too much viljamovka. But the resulting synthesis, for us, is a veritable feast of signposts for further study, further broadening of mind.

With skull imagery always comes the enigmatic scene of Hamlet with Yorick’s skull held aloft. Earlier in Hamlet, the titular Dane refers to the encasement of his mind as a globe (no doubt a play on the venue in which the play was performed). The mind, then, is a symbol of confinement–Hamlet’s nutshell. In Harsch’s book, the image of the skull is conflated with that of a prison. “Islands are perfect prisons, for the mind so readily adapts itself to the idea of isolation…” The mind, here, is “happily trapped in his skull,” and can be counted as king of infinite space. The paradox of slave and free man.

The Driftless Trilogy

Taking matters into my own hands has proven most deeply satisfying with the disinterment of my first three published novels, The Driftless Zone, Billy Verite, and The Sleep of Aborigines.

I haven’t mentioned yet that both The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas and Walk Like a Duck are Not for sale in the United States. Or have I? Anyway, the point is that I want very badly for a publisher to take them. Therefore, they can only be sold in ratlined samizdat fashion.

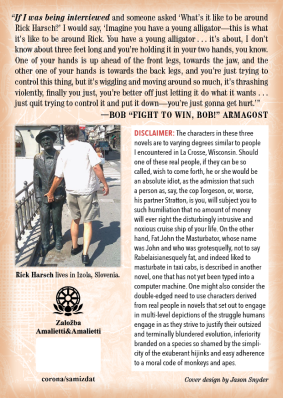

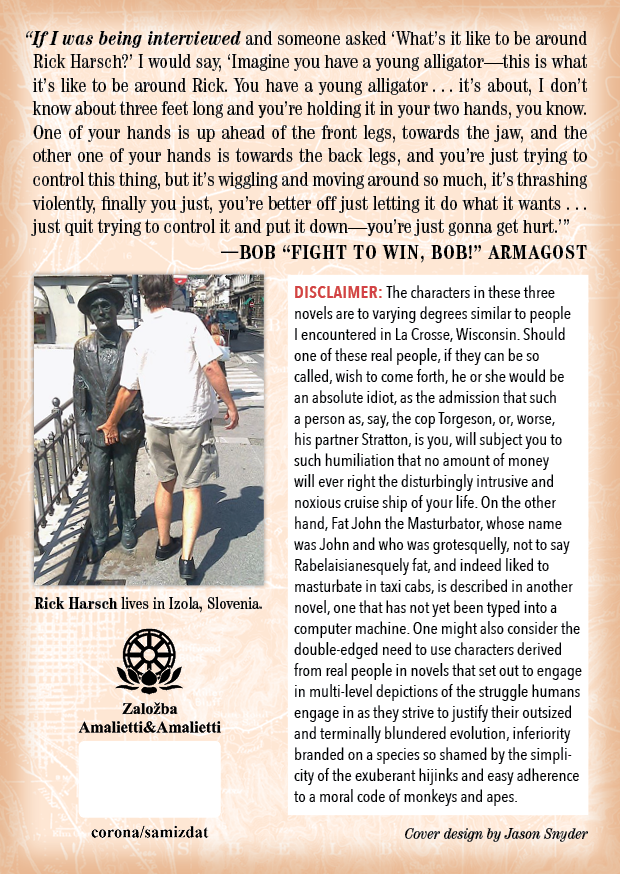

That said, I frankly don’t give a damn if anyone buys a copy of The Driftless Trilogy. I’m content to have it all over my apartment, with the cover designed by Jason Snyder and it’s shadow of a roach, the blurb by the unknown James Adler, who is not a writer, or not yet anyway, and with the back of the book which defies conventional presentation.

Blurb of the author, disclaimer serving as descriptor, and Jimmy by the crotch in Trieste.

All three novels are satirical noir, Menippean to varying degrees. All are funny, and though it was 20 years since the publication of the first, The Driftless Zone, that I read them in print, I enjoyed all three thoroughly–in fact, was surprised at their combinations of humor, philosophy, raunch and revelry, the optimism of their pessimism, their inventiveness, the rules they gleefully broke.

So here I will just provide a brief excerpt from each:

The Driftless Zone: A cock is a big mean chicken worthy of respect. Spleen’s old man had his first heart attack while trying to bludgeon a king rooster named Wes.

Billy Verite: “Biliary dyskinesia, that’d be my guess.”

The Sleep of Aborigines: And death only is the sleep of aborigines.

At least two books will be published in the fall, a romp of satirical heft by the Slovene Bori Praper, and the third novel of the underknown, if highly noted, Jeff Bursey. With luck, more will be offered as well.

rick harsch, July 12, 2020