Introduction

—Rick Harsch

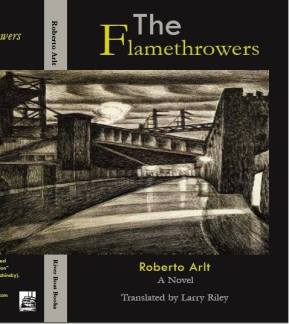

- The Flamethrowers, by Roberto Art, originally published in Buenos Aires in 1931, is without question the most important Spanish language novel unavailable in English translation.

- The Seven Madmen, considered by English language literary critics the most important novel written by Roberto Arlt (published originally in 1929 in Buenos Aires), has been translated twice.

- Neither book is a novel.

- The Seven Madmen is the first half of a novel and The Flamethrowers is its second half.

- Roberto Arlt knew this. And I have no doubt that Julio Cortazar and every other Spanish language reader inspired by Arlt knew this as well. And since Arlt is considered a precursor to the ‘Magic Realist’ boom in Latin American literature, some would say its godfather, this strange fact of its botched delivery into English is an obscenity not without charm.

- In fact, Arlt likely published the book in two acts as he did for financial reasons. And of course it is for financial reasons that no one has bothered to publish The Flamethrowers. (Our translator, Larry Riley, knows more about this, for in addition to the difficulty of selling obscure translations, it seems there was a difficult heir in the Arlt family.)

- Certainly the two translators of The Seven Madmen—Naomi Lindstrom and Nick Caistor—knew that they were not really translating a whole novel. Arlt said so at the end of The Seven Madmen. Lindstrom and Caistor had to translate this: ‘*Commentator’s note: The story of the characters in this novel will continue in a second volume, The Flamethrowers.’ If that seems ambiguous it is because the commentator is unfamiliar to you as a voice who is telling this singular and, if multi-splenetic, single novel. And then there is that most benignly adamantine voice among Arlt’s nephews, Cortazar’s, in his introduction to the latest publication of The Seven Madmen (in English), referring with casual authority to ‘…what is in truth one novel with two titles.’

- Arlt’s novel is unusual in that it is imbedded in time from which he deracinates his characters.

- The Great War provided urgent impetus to Arlt’s characters; they viewed the horrific episodes of World War Two with wry, sating curiosity despite Arlt’s grave.

- Born in 1900, Arlt died in 1942.

- The Enigmatic Visitor of The Flamethrowers was not surprised that atomic bombs did the work that a few dedicated madmen with phosgene could easily have accomplished.

- Early in The Mad Toy, Arlt’s first novel, a group of visionary urchins forms a club, at which the following, among other, proposals is made: “The club should have a library of scientific works in order for its associates to be certain that they are robbing and killing according to the most modern industrial procedures.” This proposal is made directly after a discussion regarding replacing a chicken egg’s natural contents with nitroglycerin.

- Circuitous routes are pioneered by admirers of Arlt to reach the point where they feel it is safe, finally, to say that his writing was, after all, human. Yet what separates Arlt from all writers of his time is his anguish that the human is finished, finishing, knocked off, an anguish that is expressed like no other anguish has ever been expressed in literature, in the character of Remo Erdosain, whose essential phenomenological disturbance is an obsessive leitmotif of The Seven Madmen, quicksand for the tender readers like myself who recognize the tin skies, cubical rooms, geometric incursions of light and thought, and, anguished, Arlt compelled again and again to describe Erdosain’s anguish, perhaps already knowing that one impending horror was the inevitable scrutiny of the actions of Erdosain by Giacommetti figures picking Beckettian through ruined literary landscapes.

- It is difficult to argue seminality, particularly in fiction, which lacks the immediacy of painting, and more—it assumes a lack of transfer between the arts. So when Roberto Arlt is credited with being the originator of magical realism, not only is the issue absurd, it serves to deflect the meaning of Arlt’s great work, The Seven Madmen and The Flamethowers. He may have preceded Guernica, but not Tzara, and not the city scapes and madmonsters of Grosz. What makes Arlt’s work great is to some degree indeed its originality, his private cubysmal canvass that combined the abysmal industrial architecture and working conditions of the most modern of human creatures with the existential madness this engendered, and awareness of historical defeat, and the other side of that, what lurked temporally beyond, the advanced cannibalism of technological weaponry and worse, the acceptance of it. The chapter The Enigmatic Visitor in The Flamethrowers in which a jaundiced, fully uniformed (gasmasked!) soldier appears to Erdosain at night, their subsequent, almost blase conversation about gasses, including the support for Erdosain’s belief in the efficacy of phosgene as a mass murdering agent, and worse, the final declaration of the visitor, places Arlt beyond the future in which he is accursed with being labeled progenitor. For Arlt, civilization is over. As he writes, it is dying a slow death, and still is. Witness the writer who perhaps best reflects the influence of Arlt, intentionally or not, Rodolfo Walsh, who in his astonishing work of investigative writing, Operation Massacre, refers to ‘…this cannibalistic time that we are living in…’, in a book that in retrospect seems to have ushered in a regime much like that of the United States, in which the faces change, but the cannibalism gathers strength, so much so for Argentina that some 20 years after the publication of that book Walsh published an open letter to the regime and left his home with a pistol knowing he was going to need it that very day—and indeed was murdered at five in the afternoon. This is Arlt’s greatness, a diagnosis not a prophecy, and an accurate diagnosis at that. In Arlt there is absurdity, surreality, some Kafka, some Beckett, some Joyce, but mostly there is what may be called hyper-reality, an umbrella term, which to Arlt was merely the horror of reality.

- In his own introduction to The Seven Madmen, Julio Cortazar, not a man to be trifled with, refers as if to a historical fact, to ‘The lack of a sense of humor in Arlt’s work’, attributing this to resentment regarding his circumstances in life (too much work to write freely, one gathers). Perhaps—I have no wish to quarrel with the master, Cortazar—it is something to do with the glimpses of optimism afforded Cortazar in the early 1980s when he wrote the introduction, but he is utterly mistaken. Arlt is extremely funny, even as he delivers the worst of all messages. Again Beckett comes up, and Kafka, both very funny men with very dark visions.

- Earlier in that same introduction, Cortazar referred to Arlt’s resentment—and again he got it wrong. Arlt was said to be a part of a circle, the more proletarian Boedos as opposed to Borges’ Floridans, each representing a part of town. To know Arlt, to know Erdosain, is to know that neither would have sought comfort in Florida (a neighborhood in Buenos Aires). And, further, to know Arlt is to know the themes that ran like wires through his life and work, his inventions, his very proletarian nature, his resentment, yes, but resentment at the state of the city, the state of the US, the condition of doomed humanity. Sure this is related to his working life—in such a condemned state, the wise man wishes to frolic.

- Cortazar’s errors are Argentine. He was born in Belgium, raised mostly in Buenos Aires in rather privileged settings. He is speculating. Besides, he shares a correspondence with Arlt that rises to rarefied spaces of affinity, that perhaps all readers find in a few authors, and he shares that affinity with me. I almost claim such affinity with Cortazar. I began his Hopscotch in 1984, read 70 some pages, leaving the bookmark in, returned to the same page ten years later and found myself immediately back in Paris with his lovers and their game of serendipity deferred. What is this affinity? Difficult to define, it is best rendered by example. I recently met a cultural and film critic living in Moscow by the name of Giuliano Vivaldi who read Arlt about the same time I first did, in the early 1990s. He was so taken with Arlt that he decided to try to translate him from the Italian, but needed to procure a copy of the rare book, so took the train from Trieste to Rome and photocopied it at the national library. Such fidelity and ambition has only been exceeded to my knowledge by Larry Riley, the translator of this copy of The Flamethrowers. Both Arlt and Cortazar would appreciate the story of Mr. Riley’s work. Not content to stop with reading The Seven Madmen, this veteran of the coast guard, at the time a postal worker, determined to translate this book from a language he did not know at all into English. He was advised by close literary friends that it was hopeless, that it would only lead to disappointment. Arlt could have told them otherwise. For such passion succeeds. And this translation is indeed a success. Mr. Riley finished the translation about 13 years ago, was told by a kind and indulgent Naomi Lindstrom, that it was good but ‘not quite there.’ Mr. Riley sat on it, put it away, one hopes with a feeling of great satisfaction, until recently I learned of his old project and asked to see his work. It arrived typed out with many errors, but was miraculously, unmistakably Arlt: I could feel that in the first two pages. I would finally be able to read The Flamethrowers. Subsequently, Mr. Riley and I decided to get the book typed on computer, which was not the first idea—wouldn’t Arlt have loved the story had we published the copy that was not quite there, that was riddled with typos…Yes, but as it turns out, the process of putting the book on computer revivified Mr. Riley, who dove back into the book and what was not quite there reached what is here, a fine translation of Roberto Arlt’s Flamethrowers.

- So who am I to write about Roberto Arlt? I plead that surfeitous affinity, combined with my own literary connection with Arlt. In my first three published novels I paid homage to Arlt by naming my characters as he so often did, by their descriptions. He had his Lame Whore, I had my Sneering Brunette; he had his Melancholy Ruffian, I had my Spleen (both I and II). Of course, Arlt is unreasonably obscure in the English speaking world and though my books received a number of perceptive reviews, none noticed the homage to Arlt. So who am I to write about Arlt? Someone with a second chance to pay him homage, someone with spleen.