Voices after Evelyn by Rick Harsch

An unsolved crime that jaundiced the way a town saw itself and its relationship to the outside world is rendered into a polyphonic, farcical, yet accurate visitation to the 1950s Midwest, where banality and inspired caprice make for an odd mix of the hilarious and terrifying.

“Rick Harsch is America’s lost Midwest noir genius, an heir to the more lurid Faulkner, an ex-pat living in Slovenia, a master of dialogue. “Voices after Evelyn” is a fictional take on true crime, and its bloody heart in the real, still-unsolved 1953 disappearance of teenage Evelyn Hartley in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Through that victimization, Harsch makes us look at other victims, survivors too, and throughout the novel, a Greek-style chorus sings songs of rage and loss and puzzlement. Voices after Evelyn is taut and funny, smart and haunting, enraging and true.”

— Daniel A. Hoyt

![]()

In Rovigo, Italy

Here are the two presses involved in publishing the book. You can pre-order from Ice Cube, but take some time to read about their imprint, Maintenance Ends…

https://www.facebook.com/maintenanceendspress/

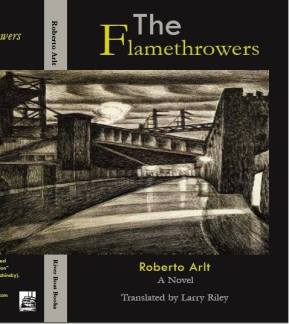

From Harsch’s other publisher, River Boat Books:

Rick Harsch on his Izola balcony with Sesshu Foster’s World Ball Notebook and The City of the Future.

[Skulls of Istria] churns in a fever pitch, soaked in liquor and crusted in dusty grit kicked up by the Slovene burja swirling through the pages. Rick Harsch, himself an American ex-pat residing in the regions highlighted in the book, has created a jolting contemplation on history and culture and violence. Sometimes it is bloody, genocidal violence but, more often in this frenzied, confessional tirade, the self-immolating variety.

As the book opens, we find an unidentified American, on the lam for sins not yet revealed, plying a local bar sot with endless buckets of local swill as he decompensates through his own checkered history. His story is accompanied by a burja – a feral wind roiling through the region that matches our man’s own discord. Early in his account, the mysterious narrator tells the story of Marjan, whose Greek fishing cap was lifted from his head by a similar burja to be blown away to a faraway inland landing spot. The hat’s improbable journey is an omen for the Odyssian voyage about to be described.

Like all epic journeys, [Skulls of Istria] is dissonant and abrasive at the outset, defying understanding; like a discordant jazz piece. But there are secret melodies to which the nattering storyteller returns, until the dissonance is synchrony.

As the harmony begins to resolve, the narrator announces a singular distaste for his home – America:

“Anyway in America the formative vary from one to one with little degree of significance. … America is the great fusion of classes by culture, the fusion of very little into nothing, a clear refutation of the more important laws of thermodynamics: there are many classes but a single caste, and money simply describes specific modalities of inertia.”

The declaration gives the reader some of the first clues about the speaker’s reliability. For, in the explanation, he sheds light on the origins of his exile, and they are self-driven.

The reader is left to wonder – and wander – with him, whether his undoing will have anything to do with a woman. Will it be Rosa? Will it be Maja? Rosa lazily fades into his life during his days in American academia. But she just as lazily fades out of it when he decamps. Maja, the schemer, blows into his life like the burja from which he is constantly on the run. Manipulating him out of his passport, she appears the likely seed of his destruction. But as he accounts for himself, he ultimately blames Kronos, his history professor mentor. Here, the narrator’s earlier disdain for American mediocrity and homogeneity begins to make sense. Kronos was unable to ever write the historical treatise which would deliver on his promise. When Kronos dies, our unidentified Ulysses finds several chapters his mentor’s writing. He takes it for his own, rewrites and completes it, and has it published. When the plagiarism is discovered, he flees. Though he isn’t able to write his own book, he still mocks and derides his mentor’s failings. All the while, he uses his mentor’s unfinished book to complete a task he isn’t capable of himself. The incongruity sets him on a journey worthy of Homer.

In the last chapters – the tale is unclear enough even to the teller that he can’t decide on the chapter’s numbering – he follows a map in search of a subject for an original work; Giordano Viezzoli a Piranian soldier from the Spanish Civil War. With the map folded into his kit, it’s uncertain whether he can actually read the map and readers are wandering (wondering) again. Is redemption the quarry rather than Viezzoli? Redemption in the spiritual since, for his sins? Or intellectual redemption? During this odyssey, he falls into a pit of skulls. And, with all his knowledge, he isn’t even able to distinguish the origin of the remains – which historical genocide produced the mass grave. All the historical violence is indistinguishable, just as his own plight’s origins are indistinguishable to him.

Within site of the saga’s end, the narrator crawls from the pit of skulls as the burja blows its last exhale. Does this mark a self-realization? An understanding? Harsch puckishly refuses to engage in that sort of ending, resolving the tale with a coin flip that always comes up heads.

This is not a book to be nibbled at, but to be swallowed whole, chewed and mashed through. The poetic word-play and sardonic humor throughout will alone keep you busy. But the real value is in the constantly shifting flavors as you masticate long after the final bite.

Bottom Line: A feverish account of one man’s odyssey through the Balkans, and through the detritus of his own life.

5 bones!!!!!

Towards the end of Rick Harsch’s new novel the protagonist – an American historian on the lam in Europe, on the Croatian coast to be precise – falls into an underground crypt filled with skulls, a depository from the long wars of Venice against Turks and Uskoks? Or a more recent ossuary of the ethnic cleansing in the Balkans of the 90s? He emerges from this premature brush with death with all his illusions shattered, his plan for a history of the region as told though the biography of a certain Giordano Viezzoli abandoned, and with a new understanding of reality, of who the people around him really are, and the role that he has played in their lives, how he has been a victim of deception.

I looked out at the world from that skull and saw first myself inert, wounded, and worst of all, a mock historian – an historian to be mocked.

Told in the form of a tavern confessional, Harsch’s novel explores issues of deception and truth, and the fraught history of the Balkans. In Vino Veritas, as the saying goes. The problem with being accosted by the local drunk, as Harsch must know full well, is that it can either be a revelatory experience, if the man can talk (and, boy, how the narrator of this novel can talk!); or it can be an evening of utter boredom for the listener and maudlin self obsessed justification for the tale teller, in which how-it happened is (in)judiciously mixed up with how-it-should-have-happened. Harsch’s tale explores the ambiguities of fiction versus non-fiction, memoir versus history, truth versus lies in prose of sizzling energy, linguistic invention, and confidence, completely at odds with the anodyne beige prose of most contemporary American authors. Harsch is a novelist whose work deserves to be better known, a writer with a style of great originality, power and vision.

“Skulls of Istria” is the spoken account of a disgraced historian in search of redemption, which comes to mean, in any sense that matters to him, an appropriate subject. He tells an uncomprehending drinking companion (the companion doesn’t speak the language, but drinks are free) how he stole his deceased mentor’s work, improved it, and passed it off as his own, to his financial gain but ultimate humiliation when the plagiarism is detected. A fugitive from the law and the bloodhounds of academic and publishing standards, the narrator escapes with his lover Rosa to Venice, a city that he loathes for its opportunistic role in history, and from there to the Istrian peninsula where he stumbles upon his subject: one Giordano Viezzoli from Piran. Viezzoli fought with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. “So this man, this 26 year old man, had left his home, gone directly to Spain and almost immediately been killed.” He would use the meaninglessness of this young man’s sacrifice on principle to an anti-fascist cause, his freedom to choose, as an arrow “aimed straight into the skull of the Fascists.” He sees Viezzoli’s “commitment against powerful forces” as “enough to bring down the moral scaffolding upholding Western Civilization” depriving “Western empires of their right to govern.” In the course of doing footwork research, the narrator literally falls into the underworld. He meets the dead, skeletal remains in a mass burial site, presumed by him to be Uskok victims of Venetian reprisals in the 17th century. Despite a strong identification with death, world- and history-weary, hunger drives him back to the world of the living where he learns that an act of charity on behalf of a new lover’s “brother” has allowed this man, whose real identity he subsequently learns is that of a war criminal hunted by Interpol, to elude capture. His principles betrayed, having ignorantly aided The Enemy, his rage turns back on himself.

For someone whose passion is for the truth, or for a fidelity to truth, which might not be the same thing, the narrator has a checkered past, given his propensity for the theft of intellectual property. But now he is nothing if not unsparing in his judgment of himself, his fellow students and historians, the empires that have laid waste their conquered provinces, preyed on, betrayed decency, fair and honest interchanges since the historians first sang their accounts of what they’d witnessed or heard. He has always been not merely suspicious of romantic love but actually contemptuous of it while enjoying the benefits that accrue to him from indulgent Rosa who supports him through the lean years that run into decades and then flees the country with him in his disgrace.

Stripped of nearly all illusions by his close reading of history and observation of his fellows, the narrator spares no one his clear-eyed assessment. Clear-eyed, yes, except that he allows his passion for “gypsy” lover Maja finally, fatally to cloud his vision. He doesn’t see what’s coming. What’s that about knowing history so that you won’t repeat it? He is being used and betrayed for his resources as surely as any of the empires he loathes betray and steal from whom they will. Though he has “witnessed” indecency (mild term) countless times in reading history, in reading newspapers, none of that prepares him to encounter something similar on a personal level. He is a man of thought, not action, as he admits, and when given the opportunity to act, he makes all the wrong choices. He does not know with whom or what he is dealing.

“Skulls of Istria” is a tour de force of compact rage that is brilliant in every sentence, in every description and nuance of character and movement. Everything is noticed, and everything means something beyond what it appears to mean. Whom can he trust in this volatile region of the world? Everyone plays his or her cards close to the chest. This novel contains some of the wittiest and most incisive observations of human behavior and human foibles one is likely to find between the covers of a book. The author is a playful linguist but rarely allows his playfulness to become an end in itself. Harsch masterfully describes thought life as beautifully and clearly as he does lived life, to the extent that I found myself reading slower and slower and marking sentence after sentence that leapt out at me for sheer rightness and poetry. No one describes a landscape, topography and the difficulty of traversing it better than Harsch. No one can write a funnier sex scene than Harsch. It should give one pause to be able to say, these days, that he or she has run across an original sex scene, given the overabundance of the same in daily life. But search these pages for just that.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough. It is short but profound, angry but funny, truthful as only the fallen one can speak the truth.

Rick Harsch’s truly excellent “Skulls of Istria” is a book that deserves to be read. This thin novel with less than 150 pages and only 6 or 7 chapters demands but a minimal effort and time investment, say an afternoon read, a few hours on the plane, for what I consider a huge return.

The story too is very readable. I mean by that, that from the first page, the author grabs your attention, you are sucked into the narrative and before you know it, captivated, you keep on reading. Or listening…, for that is what you actually do, you listen to a narrator babbling away while he drinks glass after glass of a local spirit.

The narrator, a self – exiled American academic, a mock historian he calls himself, speaks to the reader from his regular watering hole, a sea front bar in the Slovanian city of Piran. He has taken refuge from the terrible Burja, a legendary storm-wind that rages outside over the Adriatic Sea.

As his voice drones away, occasionally interrupted by his regular trip to the bar’s toilet to relieve himself, you install yourself in comfortable passive listening. But that may be a dangerous lapse of attention for you should listen carefully; close reading is required. The story the historian tells might after all not be as innocent as it is narrated and the steady downing of brandy might not only help the narrator to find his words but maybe also give him the necessary courage to proceed.

The American is basically and safely speaking to himself, for the other person at his table appears to be dead drunk and the other people present in the bar mind their own business playing cards. Anyway, nobody is eavesdropping, and we start following the narrative…

From innocent and funny anecdotes about the excesses of the Burja wind, the storyteller comes to tell us bits of the very violent history of the area, mingling it with his own confessional story of how he washed up in this coastal Istrian town. The man’s story consists of different threads that loop and snake around each other : the reason of his self inflicted exile, his relationship with his traveling companion, his passion for a gypsy women and his desperate search for a historic topic for a book he wants to write.

All this is recounted in a succulent flow of words, full of puns, clever wordplays, literary trouvailles and newly chiseled porte-manteau words. Not only does the narrator’s story turn out to be more than just interesting, it is darkly sarcastic and funny too.

As the reader starts to unravel the separate threads of the narrative yarn, a Hitchcockian structure appears that increases the worrisome mood permeating the pages of the book. The historian seems to have forgotten that what is the past today was the actuality of yesterday. In an area with a history of violent ethnic war, this is a warning not to miss.

Hell under one’s feet, might be but just a drop away.

A must read.

Skulls of Istria takes us from a midwestern academia to the Adriatic coast of Slovenia…where an on the lam would be American historian after some nefarious doings on his part having washed up with his girlfriend like two bits of flotsam and with vague notions of starting over. And so the historian sits in a bar in Piran (a smallish Slovenian town on the Adriatic coast) plying a stranger who doesn’t speak a word of English with drink while regaling this stranger with the trials, the vicissitudes of his past and how he came to be where he is–abandoned and adrift in a foreign land and among strangers who for the greater part he has some difficulty communicating with and/or understanding is also part of the confession he feels compelled to dump on his uncomprehending (and probably could give a shit less) drinking buddy. His burdens need to be unburdened out loud and what better place than a tavern? Language, politics, culture, love blending into each other as the burja blows sometimes so powerfully that it can lift a truck off the ground…all the while that the historian’s sardonic black humor pricks away at his own conscience.

While a comparison could be made to the prose device Camus creates in The Fall–one does get the sense that Albert’s hearer is at least sympathetic. And then Camus was always kind of dry to me….which is why he will alway be best to me with large sandy landscapes looking off towards infinite vistas rather than in Amsterdam bars or any bars for that matter. Skulls of Istria works better–much better in fact because Rick Harsch’s prose style breathes life and humor into it. I mean really to me you need atmosphere to carry this off right. That the listener is only interested in drinking himself into oblivion while the historian rattles on and the burja blows as background noise is just one ironic twist but it welds the book from beginning to end.

IMO there are very few really great American fiction writers writing today and Mr. Harsch (a longstanding member of the LT community) is one of them. His stories are replete with intricate plots, interesting characters, modernistic twists in both action and language. I’ve read several of his works and Skulls shows a great writer at the top of his game–at least until he tops it again–which I suspect will happen. This book would be a great place for someone new to his fiction to start.

)

)

The last book I read in the English language was over four months ago and the first book I picked up after this sojourn was Skulls of Istria by Rick Harsch and the second book I picked up was Skulls of Istria by Rick Harsch, thats right I read Harsch’s novel and was so impressed I immediately re-read it. Being a little out of touch with the English language in novel form, may have helped because Harsch bends and twists his words in ways that gets the most out of them, for example:

“How many secret stercoricolous tribes of coprophagi have lived and died unknown”

Perhaps the most disgusting sentence in the whole novel, but at the end of the day I am glad that those tribes lived and died unknown.

Weighing in at 144 pages the novel is not one to exhaust the reader or lead him to regret that time may have been misspent, because the curious thing is that it is also very readable and because I was so fascinated by the word play on that first reading I imagined I might have missed some fundamental themes and a good story and so when I re-read it I found I this to be absolutely correct.

Novel writers live by the art of their story telling and this novel opens with the Speaker/Author inviting a customer at a waterside taverna to sit at his table while he plies him with drinks and proceeds to spin his tales of loves lost and won, plagiarism, intrigue and murder with dollops of Balkan history and a background of a rugged terrain. The speaker/author is an historian (perhaps the best story tellers) with particular knowledge of the coastal towns of Croatia where much of the action takes place, but the speaker/author is also an American and he brings with him the persona of a life time battle with “Uncle Sam”. This is not a two way conversation as the author/speaker says to his guest:

“ But lets not talk politics, you and I, In fact I’d rather you not talk at all, you just listen, I’ll talk.

And talk he does; about the Burja wind, about the history of the peoples living along the coastline laced with passing references to the story he really wants to tell: how he became victim to the machinations of people still trying to escape from the aftermath of yet another vicious war in the Balkans. He tells of his academic career in America his fascination with the war torn region, his attempts to write a masterpiece, the plagiarism that led to his fleeing the country and landing up in Croatia with his partner Rosa. In Croatia he finds a subject on which to hang his chief d’oeuvre, but he is seduced by the gypsy-like Maja who involves him in a Balkan intrigue all of his own.

So what better way than to spend an afternoon sitting at a table opposite this voluble American while he plies you with drinks and tells stories that will shock and awe you, that will drip with the harshness of a people and their surroundings and the history that no one can escape, but underneath there is also a human story of love and lust and that age old conundrum that concerns so many writers: the search for a subject that will satisfy the serious artist. Mr Harsch is well on the way to finding that with this novel whose individual voice will fascinate and entertain the reader in equal measure. Highly recommended and a five star read. ( )

)