KATABASIS, a THEME for TRIESTE

By Rick Harsch

With Photographs by Jan Skomand

KATABASIS: a Theme for Trieste

Humans are evanescent; cities are an attenuation of that being-tainted evanescence, a smart ape-group’s struggle against disappearance. Cities outlast us, and that is by nature mystifying, and we know that nothing about the city is humanly known on that very level which is the only one where what it is exists. So we haunt them with their own pasts, pasts of which they are well rid, as cities are the best humans did at approximating nature, which abhors an eternity. Cities are born to die, are ready to die, and they do—all—eventually die. Yet it is no paradox that in their dying cities produce great bursts of life–the metaphor brought to mind is rats taking torches to the armories—the humans in the cities have no urge to measure their currents against the crepuscular flex of the city. Mirrors don’t reflect honest decadence. And if humans be the strangest of earth’s creatures, and they certainly are, and if each city harbors tortoise-like lunatics (always men, for some reason) who persist in splendorous pigeon-cursing pique, insistent that the city must die first, the simple truth is the city will survive them all.

Nature perhaps as well coerces writers into anthropomorphicizing cities, as I have just done. The worst and most often inaccurate example is to call a city less vigorous than it once was a dying city. I need no other example than the subject of this book, Tergeste, Trieste, Trst, a city that has been associated famously with nowhere, and is considered internationally to be a dying city, if not a dead city. This should come as a surprise to the quarter of a million residents of Trieste—a number, after all, great enough to succumb to holocaust—but it is a cliché they live with; or live beside, for in their quotidian it is doubtful Triestini give much thought to the morbidity of their city. I am not a Triestini, but as a New Istrian living nearby in Izola, Slovenia, working in Trieste, visiting often, I am truly sick of the lack of inspiration behind the common misperception of Trieste. I would go so far as to call it inhuman.

The reason for the persistence of an insipid human myth is the lack of a vibrant newer myth. That, simply, is my diagnosis of the problem of humans and Trieste. Once the fevered, international port lost its hinterland—political economy turning a cold shoulder to geography–the city naturally changed dramatically. That it had also become something has been strangely overlooked by outsiders. Every city has its character, every neighborhood its character, and so every city its mischaracterizations. Thus I will make no attempt to determine the character of Trieste. I intend only to posit a theme for a city visited famously, and inarguably, by a unique and violent wind, the bora, a katabatic wind, Alpine air sucked down to replace languid Mediterranean vapors, knocking over old ladies and bicyclists, occasionally flinging a roof tile through a neck (Prague has its defenestrations, surely exaggerated; Trieste its decapitations). This wind is yet more powerful in metaphoric state, as witness the case of James Joyce, the most internationally famous historical Triestine, whose Trieste Katabasis is legendary and was of such force he put the protagonists of his final two books through much the same—Bloom, of course, as Ulysses had no choice whatsoever; and nor did Finnegan, the legendary drinker who went so far as to die so as to get himself a decent splash of whiskey.

I must immediately take a sword to that last paragraph. Off with Joyce’s head—that, too, is katabasis. The finest book on the phenomenon is The Colossus of Maroussi by Henry Miller, who leaves the reader deceived into a state of static euphoria, mopping the forehead with a handkerchief, the journey having gone well. It wasn’t his fault, for Miller knew that katabasis was very much like a carnival ride assembled by the drunk, blind and demonic. For some descent was arduous and rewarding, of course: for others it was a headfirst plunge into a karstic hole, a foiba…And we will indeed get to that perpetual katabasis in time, smrt fascismu! and pace nel mondo.

Meantime I cast ahead of myself, having heard from Mac, the gent from Ghent, who inadvertently warned me off the ratlines to the buried magazines. ‘I have been re-reading the text you sent me more carefully,’ he wrote, referring to just the first three paragraphs; ‘Katabasis was for me, monomaniac mariner, only a wind, a dangerous one, but predictable in its unpredictability, like a Venturi. But that was too easy…I suspected. And suspicious I looked up Katabasis and found that it firstly meant going down (to the underworld) or toward the coast…as opposed to the Anabasis of Xenophon’s fame…’ Naturally, all that Mac suspects of my intentions is true enough…true enough: strong words for modern man. Yet there is also simply Trieste mundane, tramontane, adamantine: within the shell of the turtle, one might say…particularly as my photographer and I began this venture with the intention of violating a minor law for luck (Mac: ‘Chronos castrated his father with an adamantine sickle.’). This involved transporting an invasive species across national lines and releasing the animals in the pond of the Giardino Pubblico at the end of Via Battisti, a park featuring the finest chapter in Claudio Magris’ Microcosmos, in which not only did I learn of the turtles in the pond but also the many busts of writers in particular, Italo Svevo in magnificence, his head having been stolen several times. I read the book more than a decade ago, probably about the time I bought the first turtle, Captain Michalis, for my son. At the time the creature was about the size of my thumb, the shape it would be if it were pounded with a mallet. A year later I bought Bouboulina for my daughter. Gradually the turtles outgrew my capacity to make for them a paradise; though the children did their part by losing interest in them within weeks, one assumes that peace and food security comes to less than that which nature invests within desires of the testudinatal race. A fair amount of swimming, the hunt…But Captain and Bouboulina ‘swam’ eventually in the largest plastic tub I could find, the fresh waters of which began turning green within a day of changing, turbid within a week, and too often were again changed only when a stranger to our balcony noted the smell. It could have been worse: Izola was until recently a fishing town, a tin cannery town, a place that smelled like fish. There’s little doubt that a degree of nostalgia drifted off my balcony as the turtles lived on as we presume reptiles do, they and their odd limb-tips half flipper/half claw, unseen under the muck layer more often than not. I know I know nothing, yet assume that the smaller-brained creatures express stress by dying: and these two always harbored great vigor. Perhaps I merely lack the culture to grow a proper disease. So I cleaned them in the shower, put them in a cloth bag, put the bag in a fittingly plastic shoulder bag, and my photographer and I drove to Trieste and made our way to the public garden. The busts stood in still heft amid more jungly verdance than I recalled, and the pond itself was fed by a spring and narrow falls surrounded by bamboo. This was going to be easy, I thought. Just above the falls was a rounded clearing over-filled with benches, where two Serbian bums were passing the day. The first asked my photographer for a smoke and disappeared once he got it. I decided not to wait for the other to disappear, particularly as he seemed to be taking some kind of interest in what I was doing, having clambered into the bamboo and down a couple stages of rocky aquadescent. I quickly removed Captain and placed him on a stone over which water ran rapidly. He remained withdrawn and the flow did not carry him to his better life. Still the second Serb observed. I took out Bouboulina. What was he looking at, really? The last thing you want when doing something wrong is to appear to be doing something wrong, so I held up Bouboulina for him to see, a gesture he mistook for an offering—‘Ne, hvala’—and I put Bouboulina in the falls, she emerged spry, and was soon out of sight. I nudged Captain a couple times with my foot as if across asphalt, and he, too, was relocated…within the safe confines of Trieste, safely apart from native species.

Goodbye, Captain.

In his prescient classic The Folk from the Earth (my translation), in the chapter “Katabasis Monterno”, the early 19th century Freiburg philosopher von Schlag (sic?) argued that prison had become the one true church of modern man, the last refuge of hope for redemptive process. As I understand the fragment (as presented by a Danish philosopher of minor repute whose name I no longer recall), von Schlag (sic?) meant to suggest that the lurch of modernity toward industrialization, away from nature, was a permanent shift, and that among the manifest changes in the totality of the life of humans was a deterioration in all aspects of the incorporeal, a degradation of myth, an interment of lore along with banishment of all mysterious in lives of the night. Yet the surpassing need for this incorporeal required that some sort of maladaptation was necessary, and so as regards katabasis, we would have prison. Sparking through intellectual history, with matted coats and corded ruddering tails, ideas provoke an excitement akin to that of the finest poetry, even if their application is a slippery matter. I’m reminded of Spengler’s unforgettable line: you can take the man out of the city, but you cannot take the city out of the man. The very sighting of a truth in that line excites me in precisely the same way I’m uplifted upon sudden glimpse of a hedgehog, or a nutria. And there is no doubt that indeed a prison sentence is an invitation to an exploration of katabasis, even on the mundane level of rehabilitation.

The Coroneo Perp Walk, Trieste Central, or where a passaggio connects the justice building with the jail.

The resonance was not accidental, for the very process of making this book began as a visit to Coroneo, Trieste’s prison, as an act of homage by my photographer and I to a forgotten wreck of a man, dead three years, likely having committed suicide by mixing heroin with an enormous litrage of alcohol. Štranzo was much despised and more feared, having a penchant and talent for fighting, a dark spirit, a drug habit, and a sensitivity to slight keener than an albino’s to desert sun. He was all the more hated socially for having squandered talents bestowed upon a very few in life: he was a rare artist, the kind of whom it is said perhaps one in a generation passes this way, with an incisive, comprehensive mind. He was invited from his home in Capodistria (Koper) to study fine arts in Ljubljana, where his impact was felt immediately, remaining even as he himself quickly vanished into a life of wandering, heroin, and brutal assaults. By the time I met him he was a new man; his time in Coroneo was enough to prevent him from beating strangers to a pulp for having the nerve to turn their eyes from him as they passed in the street. His sentences often ended with ‘…don’t want to end up back in jail.’ His attraction to me is of no importance, as my whole life I have been singled out by the odd, the lame, the demonic, the deranged, the needy (I could provide example after example: the one guy on that plane, that train…the oddity places me in a class of some sort with a speculative Jesus: For instance, over the span of my 58 years, at least 20 people have had me touch their head injuries, most recently a former Yugoslav reporter who had been shot in Prague by Russians in 1968. That was not yet two weeks ago.). Importantly, I did not fear Štranzo; that was surely one pre-requisite. Another was an interest in literature. My photographer shares these, and he, quite separately, had been a friend to Štranzo. In my apartment, Štranzo was gentle with my children, physically loving to my dogs, and could not help but exude the atomized stigmata of one often forced to leave. He never wanted to be unwelcome in my apartment, and even if he was not one to yield to anything at all he could not prevent my knowing that. Perhaps that has nothing to do with his scattershot tendency to bear gifts—often spectacles of nature like giant donkey ear seashells that washed up one day, impossible plants that, like him no longer could manage an effort to take root. And one night, it was past three in the morning, he buzzed me awake and arrived up the stairs with a holiday display size Italian flag and these words I will never forget, ‘I thought you might want this.’ Humans disguise an incomprehensible nature by a surface complexity, yet when it comes down to it we are no different from dogs sniffing each other’s asses. On the great dogwalk of life, Štranzo and I sniffed each other and found a short couple years of simpatico available. But he was never happy, and he spoke to me too often of suicide. He was off heroin but hooked on morphine and the last year of his life he kicked morphine but needed all the more alcohol. Suffice to say what would have been required for him to live as an artist was beyond his means. For Štranzo, katabasis was welcome torture from which he emerged with terrifying eyes he covered with sunglasses. Coroneo was easy by comparison. He simply did not want to return and so only engaged in violence far from crowds. He described one of these fights, at a house out in the foothills inland—a butcher knife and another two appliances were involved and he had to restrain himself from killing the man. I am not certain, but I think a woman who didn’t much care who lived through the battle was in the bedroom in a state of low alert at the time, and I think Štranzo intentionally provoked the other guy by having sex with her, that in fact he had sex with her entirely for that reason. He wasn’t a saint. So when he died not many people cared and too many were simply glad of it. A detail from his life that was surely more important than any other was that when he was 21 his twin brother, Branimir, by all accounts a talented and kind young man, leapt from the bells of the campanile in Capodistria in Tito Square. That, too, is katabasis.

The people will decide if this is a hall of justice or not.

My photographer and I visited Štranzo’s favorite spots in Izola and Koper, but also felt that no day of homage would be complete without also seeing Coroneo. Our directions were vague enough to bring us to the intersection from where this photograph of the hall of justice was snapped. We asked for directions, unaware that were actually at our destination—the prison connected to the building at its rear. The grandeur of the building was lost on me, putting me off only so that I wished to hurry on, and we did, finding ourselves on the other side, where the ‘entrance’ to the prison is hidden behind a row of trees. We found a guard, and as my photographer speaks Italian, ‘we’ asked about Štranzo, who had been out for at least seven or eight years by then. Describing Štranzo’s loose-limbed build began the process of remembrance, but it was the combination of his wild nature and loud voice that finally did it. The guard smiled. Sure, he’d had to club Štranzo a few times. There was genuine affection in his recollection.

I got to thinking and we got to talking. Trieste had been of interest to me since I had seen the last page of Ulysses at a time when the city had far more poetic meaning to me than locational precision; but it was that building, its grandiosity not grandeur, the conceit of any building allowed to label itself justice, it was that more than anything that was the final lure to writing another book about a place. And of course I had never been comfortable with the title of the Morris book, the tendency of Trieste to be known so little for so little and still gotten so wrong, and…I have no wish to be immune from the charms of urban history. Yet the incipient fascination of a naïve writer, in that last exalted stage of any author of profane books, remains an immeasurable lure, a powerful if mundane loci, a bottom toward which to plunge having found myself living on the Gulf of Trieste for reasons having nothing to do with this city that had taken on a mystique particular to my inchoate yearning. Earthly connections are available as stars, and it was a simple constellation for me to label: Joyce, upon landing in Trieste, was arrested within two hours having inserted himself somehow into a melee in Piazza Unita. He did not find himself held in the Coroneo, but neither are the stars of Orion actually neighbors. Another way to express what I am trying to suggest is that nothing arose to prevent the momentum that was gathering toward my writing about Trieste.

Why did I forget about Zurich and Paris?

Last night my daughter, Bhairavi, and I took one of our dogs, Sultan Suleiman, for a swim, on the way running into an adolescent rat just in front of our apartment that our hound had trouble focusing on as he is a creature of habit. The rat was running along the curb of an island of flora where Suleiman tends to relieve himself, and though the creature was scooting along with elaborate ratleggery, Suleiman missed it. Only when the rat sensed my vigilance did it begin to consider the need to escape, and, being a rat, it made a maze of the matter, turning abruptly and running back the way it had come. Only then, at excessive urging, did I get Suleiman to notice. He chased the rat from the labyrinth of its eventual demise, the creature leaping the curb and disappearing into undergrowth. At the beach I found the usual beached-home shell and bit of sea-polished glass with which to decorate the photo, which includes the type of book that I have no desire to write simply because so many already exist. Which is the reason that I asked Juan Vladilo, astrophysicist working in Trieste, if he would give some thought to places in the city that are of some interest yet generally not already covered in books. He promised to do so, and maybe feeling a measure of gratitude, I finally, after knowing him nearly ten years, asked him where his observatory was located. ‘Near San Giusto.’ ‘Where’s that?’ I asked in all my innocence. His eyes widened, which probably came naturally to him as one learns early not to squint when looking through binoculars and telescopes. ‘You’re going to write a book on Trieste and you don’t know where San Giusto is?’

His words had the effect of a sudden flaring match light in a darkened warehouse. Oh yes! Absolutely. Thank you, Juan, thank you, went my silent exuberant writer brain. Yes, that is precisely the way to write about San Giusto. Every book about Trieste includes San Giusto—they must—for San Giusto is indeed among the most important locales in the city, historic, palimpcestual, enduring! Central! Yet this city I love and with which I have now been by degrees intimate for seventeen years has kept San Giusto hidden from me. Certainly Morris wrote of it, though it would not be odd if my intermittent disgust with Morris’ love of empires had me yawning just at that point. And my extensive reading about and around Trieste would have been more focused on questions like why this armpit and not the other (Genoa)?, antipathies from Guelph and Ghibelline to Brit and Yugoslav, motifs like Trieste as serendipitous non-island in Venezian sea and bandits and banditry awash in bandit sea, not to mention the city as one flashpoint of horrors in the 20th century.

With extra attention I proceeded to read all three of Italo Svevo’s novels. What did San Giusto mean to Trieste’s greatest novelist? I had prepared myself for the answer without realizing it, for after six years outside a classroom as a result of a modern drought, what the world of cities calls an economic crash, I had just last year been hired to teach mariners English in a Habsburgh structure on Piazza Hortis, where a full body statue of Svevo presides, and every time I passed him I patted him on the shoulder. The man of the city is as fond as the preceding agrarians of speaking of fate and arguing whether coincidence exists or not. I weigh in here only to mention my luck: teaching in the same square that was chosen for Svevo’s statue! Oddly, I think, in three novels Italo Svevo never mentioned San Giusto. In fact, if Svevo were one’s guide, Trieste was the Corso—and no one seems to know where that now is—the public gardens, and the bourse, not to mention the boudoirs…This, of course, was the answer I sought, which is not to say that Giovanni Vladilo was wrong.

Dear Italo.

The acrobat of impermanent emotion given the illusion of permanence is appreciated by the author.

Particularly as there are other explanations. Consider this: when reading about the 4th Crusade one is likely to recall the image of the blind 90 year old doge, Enrico Dandolo, stepping ashore onto a bloody Constantinople rock to the deafening (he was not yet deaf) noise of thousands of men clashing, screaming, heaving, swiping, swearing, dying, bemoaning, of women screaming in terror, or future explosions the battle insistently beckoned, or immediately look up at the wily, acrobatic Venezians, there masts makeshift boarding planks, or mathematically oriented, determine the number of dead required to successfully storm and take a certain tower…What you will not read of is the goings on in the Hagia Sophia. And so when Dandolo began this bizarre, revolting venture by calling on subjects of the Istrian peninsula and citizens of Trieste and Muggia in a panic sought to pacify the old murderer with elaborate shows of humble adoration, one is not likely to imagine the scenes so far as to include San Giusto, even if there is actually some chance that, if the doge were indeed invited ashore to be feted, San Giusto may have been the chosen site for a banquet and obsequies.

And unlike Hagia Sophia, San Giusto does not stand out to most self-sufficient visitors to Trieste. If it did, I would have seen it and asked after it. It is an old castle near shore after all. Quite likely when it was built, this problem was not foreseen. But over time, especially concentrated Hapsburgher time, numerous buildings of bulk and height came to line the shore of the port and move towards the hills, surrounding San Giusto entirely, so that by now the castle is far closer to the sea (where the riva runs a line sw to ne) than to the eastern boundaries of the city. I’ll illustrate this in a moment, but first, to supplement the nature of such oddities I offer this photo for consideration:

Trieste seen from the first Servola off-ramp.

Cities of broad shoulders and industry, cities of industrial birth and skyscraping adolescence, even premature sulfuric old age, suffer little aesthetic damage from incongruity. After admiring the finest skyscapers of Chicago, one does not find the related conglomeration of plants built to convert raw materials into gold turning the skies of Gary, Indiana, death-greened colors that mirror Lake Erie’s cast just before the fire breaks out. Old cities don’t have that luxury. The modern stands out as in the above picture of the back of a grocery store, a plain brick building, sports stadia with their lights, apartment blocks, a relatively modern hospital in the back ground. It is by no means a pretty picture. (Fear not entirely for the vagaries of the sea plump for the ghosts of their land structures, imbue them with ghostly wonder.) Yet ugly that picture may be, Servola is integral to Trieste, as I found when I began driving there three or four times a week to meet people whose son and my own engage in an obscure rite I am not at liberty to reveal. But that particular picture is here in relation to San Giusto for it includes a remarkable structure I only recently identified. That brick building is the Risiera di San Sabba, the only operative crematorium in Italy during World War II. This is upsetting to many Triestini, quite naturally. In fact, one necessary acquaintance, Normanno, became highly agitated when I explained that I had procured the photo, taken by my photographer. ‘I will invite you and your entire family to dinner and then take you to San Giusto…’ he objected. He did not understand, he claimed, why this building had a place in my book. Interestingly, two days later I just happened to discover that he had once taken his daughter to Risiera di San Sabba as an object lesson of some sort. (You think your life is bad…) Of course, I had read much about Risiera di San Sabba, and knew it was somewhere within a couple miles of where it is and had intended to visit at some point, when this book dictated. After all, the worst sort of katabasis may be either dying in such a place or surviving confinement there. Yet I found out it was part of my routine in a sense during the whole time I was meditating on San Giusto and what it meant that I had never focused on the place. Normanno argued that Risiera di San Sabba may as well not have been there at all. ‘The Germans did that, not the Italians.’ Now this is sensitive topical territory we will negotiate often in this book. For now, I will say that yes, Germans did, predominantly, ‘do’ that; but they did that with their own SS, Ukrainian SS, Austrian SS, and Italian SS. Why so disturbed so nationalistically? The gauleiter of the littoral at the time was Odilon Globocnik, a murderous swine who was half-Slovene and half-Hungarian. I can’t speak for Hungarians, but I know that no Slovene feels shame or complicity because of the involvement of the bloodthirsty Globocnik’s paternity. The engineer in charge of building the crematorium at the old rice husking plant was German, a serious man known for his many human-killing ovens, chiefly in Polish territories, Erwin Lambert. I suggest that for Normanno a walk through the Risiera di San Sabba would serve as a healthy katabatic experience, and given the torments endured at the risiera, the child’s skull kicked in, the elderly man beaten to death, the slaughtered, gassed, humiliated, rat-bitten, burned alive, the permanently traumatized,

***

A necessary pause for beauty that survived all the monstrosities visited upon Trieste and those people in, out and throughout the town.

***

the raped, stabbed, shot, beaten to death with shovels, gun butts, bricks, the cremated, partially cremated, the gassed, Normanno might come to distantly if perhaps only subconsciously understand what the Dante he certainly has memorized once endured.

Clearly, then, cities all have their secrets, multitudinous, and selective in the subjects who will receive their revelations. I showed the photo of the Risiera to a French Triestine who had somehow, despite a restless and exploratory nature, not yet been to see it in nearly ten years residence in Trieste. ‘That is the Risiera?’ he exclaimed. He had seen it more often than I had and yet had never seen it. This is a very simple explanation for my own ignorance of San Giusto, as you can see. I was told that on Molo Audace, the nearest pier to Piazza Unita, you can see San Giusto, but even there lies a problem.

The Ugliest Building on the Riva. I have yet to decide whether to expose the hideous frontage of the building seen above facing the sea. The orange and brown monstrosity is so ugly that it has become for me the most recognizable lump of Trieste. The Audace pier lies off the riva perpendicular to that building, and it is between that building and its neighbor that one can spy sections of the castle of San Giusto. Yet such is the hideous nature of that building, its dull brown haircut and bland, not to say uninspired, façade, that the eye is either drawn to it perversely—directly–as the stomach churns or seeks desperately a sight far off in any other direction. This is perhaps the only time when one such as I could appreciate Mussolini’s victory phallus to my left, or, the other direction, the more humble lighthouse near the old train station. The last possibility is that my eyes would linger on the building, retaining their sensitivity, their desire, in order to alight on some wonder beyond.

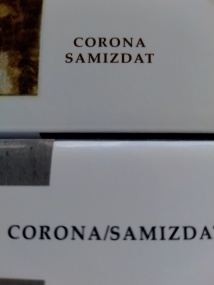

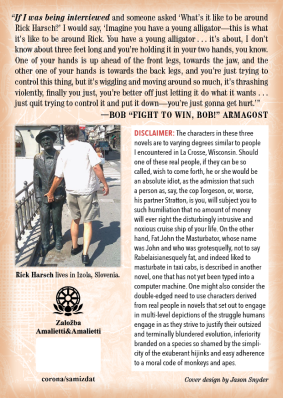

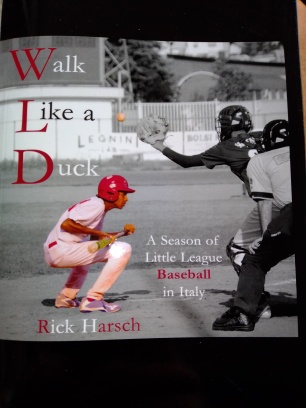

4. Skulls of Istria, by Rick Harsch, pocket size, errata slip, 175 pages. 10€/10$

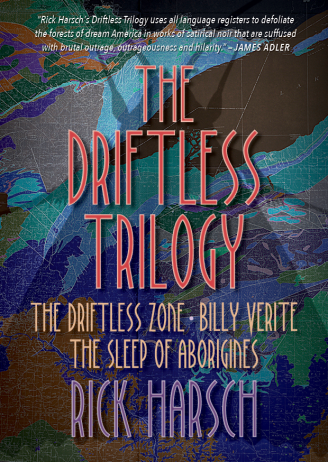

4. Skulls of Istria, by Rick Harsch, pocket size, errata slip, 175 pages. 10€/10$ 5. The Driftless Trilogy, by Rick Harsch, pocket fat size, 725 pages.

5. The Driftless Trilogy, by Rick Harsch, pocket fat size, 725 pages.

David Vardeman is by birth an Iowan, by nature a fricasee, an author of imperturbable visions. I am still waiting for an independent review of his book to appear. Til then, I am his greatest known fan, and I suppose it would seem a bit incestuous for me to praise his work here where I have no idea whether you are interested in an elusive blend of surreal, hyperreal, and the Beckettian banal, in a novel and stories laced with venomous and quirky surprises, psychological insight moving about on artificial limbs, folly modernized into uncontrollable higher gears, a book I could as well introduce by quoting his Mr. Perlmutter’s introduction in a boardroom “…allow me to introduce my father who today has joined us in his magnificent pig’s head.”

David Vardeman is by birth an Iowan, by nature a fricasee, an author of imperturbable visions. I am still waiting for an independent review of his book to appear. Til then, I am his greatest known fan, and I suppose it would seem a bit incestuous for me to praise his work here where I have no idea whether you are interested in an elusive blend of surreal, hyperreal, and the Beckettian banal, in a novel and stories laced with venomous and quirky surprises, psychological insight moving about on artificial limbs, folly modernized into uncontrollable higher gears, a book I could as well introduce by quoting his Mr. Perlmutter’s introduction in a boardroom “…allow me to introduce my father who today has joined us in his magnificent pig’s head.”

or maybe this one

or maybe this one

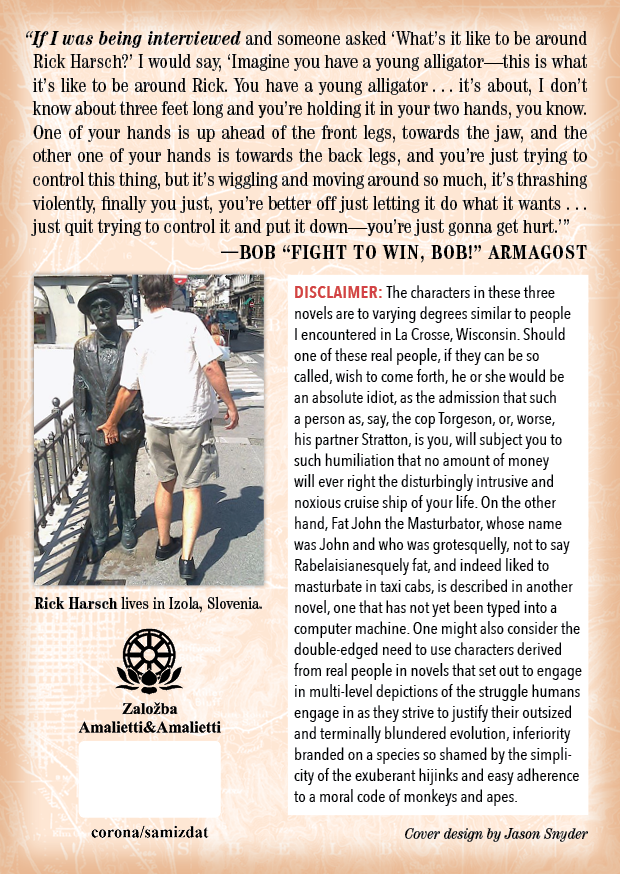

Here's the blurbery on the back cover:

Praise for Rick Harsch:

Readers, don your thinking caps and hiking boots, for The Manifold Destiny of

Eddie Vegas is an epic journey through Harsch terrain, where at any moment

language erodes into a mindscape of hoodoos and canyons—not unlike that

geological fantasia, that palimpsest of usurpation: the American West. In an era

when many writers concoct their trifles inside the cosseted lairs of academia,

Rick Harsch is a refreshing counter-example, a chronicler of our nation’s nightmares from his balcony overlooking the Adriatic. You hold in your hands a

nuclear apparatus of a novel, operated by characters all too aware of what their

futures promise—like Rowor, the tongue man of the Nimíipuu, a night-languaged injun who befriends Hector Robitaille, the bear-mauled, buck-skinned

ancestor of Eddie Vegas. Harsch weaves the roughhewn with the recondite like

no other living novelist of my acquaintance. You will revel in his century-shifts,

vast erudition, and the cock-eyed, half-cocked ardor of his men and women.

—Scott Coffel, American poet and author of Toucans in the Arctic

(Etruscan Press, 2009)

“I think that once in every generation a few writers appear with the talent,

brilliance, curiosity and DRIVE to dare to go their own way, to follow the lead

of their own imaginations. I believe that Rick Harsch is of this group. In my

view, Rick Harsch is one of the most talented and interesting young writers it

has been my privilege to meet in all my years at Iowa.”

—James Alan McPherson, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1978 for his

short story collection Elbow Room (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1977).

EXCERPT (one of my favorites):

Here's the blurbery on the back cover:

Praise for Rick Harsch:

Readers, don your thinking caps and hiking boots, for The Manifold Destiny of

Eddie Vegas is an epic journey through Harsch terrain, where at any moment

language erodes into a mindscape of hoodoos and canyons—not unlike that

geological fantasia, that palimpsest of usurpation: the American West. In an era

when many writers concoct their trifles inside the cosseted lairs of academia,

Rick Harsch is a refreshing counter-example, a chronicler of our nation’s nightmares from his balcony overlooking the Adriatic. You hold in your hands a

nuclear apparatus of a novel, operated by characters all too aware of what their

futures promise—like Rowor, the tongue man of the Nimíipuu, a night-languaged injun who befriends Hector Robitaille, the bear-mauled, buck-skinned

ancestor of Eddie Vegas. Harsch weaves the roughhewn with the recondite like

no other living novelist of my acquaintance. You will revel in his century-shifts,

vast erudition, and the cock-eyed, half-cocked ardor of his men and women.

—Scott Coffel, American poet and author of Toucans in the Arctic

(Etruscan Press, 2009)

“I think that once in every generation a few writers appear with the talent,

brilliance, curiosity and DRIVE to dare to go their own way, to follow the lead

of their own imaginations. I believe that Rick Harsch is of this group. In my

view, Rick Harsch is one of the most talented and interesting young writers it

has been my privilege to meet in all my years at Iowa.”

—James Alan McPherson, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1978 for his

short story collection Elbow Room (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1977).

EXCERPT (one of my favorites):

)

)

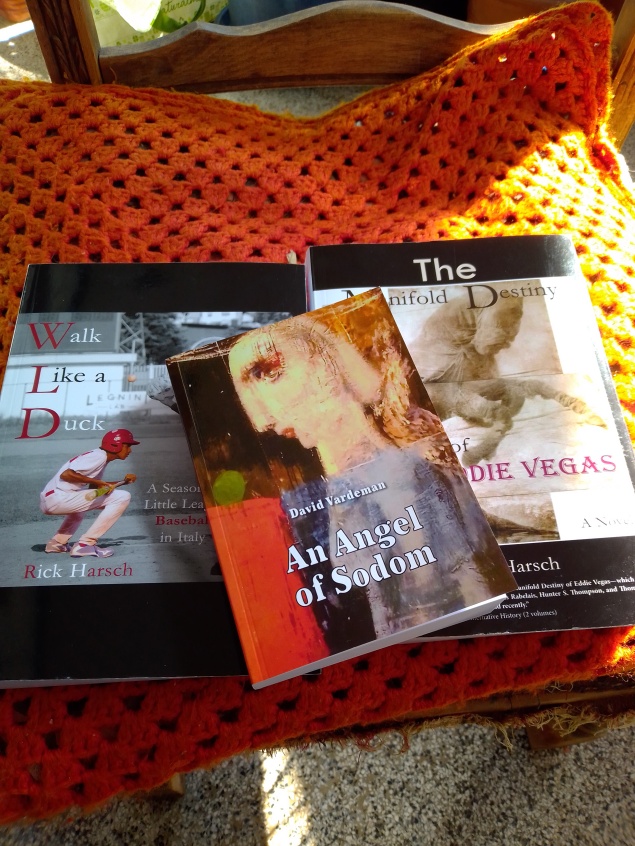

The last book I read in the English language was over four months ago and the first book I picked up after this sojourn was Skulls of Istria by Rick Harsch and the second book I picked up was Skulls of Istria by Rick Harsch, thats right I read Harsch’s novel and was so impressed I immediately re-read it. Being a little out of touch with the English language in novel form, may have helped because Harsch bends and twists his words in ways that gets the most out of them, for example:

“How many secret stercoricolous tribes of coprophagi have lived and died unknown”

Perhaps the most disgusting sentence in the whole novel, but at the end of the day I am glad that those tribes lived and died unknown.

Weighing in at 144 pages the novel is not one to exhaust the reader or lead him to regret that time may have been misspent, because the curious thing is that it is also very readable and because I was so fascinated by the word play on that first reading I imagined I might have missed some fundamental themes and a good story and so when I re-read it I found I this to be absolutely correct.

Novel writers live by the art of their story telling and this novel opens with the Speaker/Author inviting a customer at a waterside taverna to sit at his table while he plies him with drinks and proceeds to spin his tales of loves lost and won, plagiarism, intrigue and murder with dollops of Balkan history and a background of a rugged terrain. The speaker/author is an historian (perhaps the best story tellers) with particular knowledge of the coastal towns of Croatia where much of the action takes place, but the speaker/author is also an American and he brings with him the persona of a life time battle with “Uncle Sam”. This is not a two way conversation as the author/speaker says to his guest:

“ But lets not talk politics, you and I, In fact I’d rather you not talk at all, you just listen, I’ll talk.

And talk he does; about the Burja wind, about the history of the peoples living along the coastline laced with passing references to the story he really wants to tell: how he became victim to the machinations of people still trying to escape from the aftermath of yet another vicious war in the Balkans. He tells of his academic career in America his fascination with the war torn region, his attempts to write a masterpiece, the plagiarism that led to his fleeing the country and landing up in Croatia with his partner Rosa. In Croatia he finds a subject on which to hang his chief d’oeuvre, but he is seduced by the gypsy-like Maja who involves him in a Balkan intrigue all of his own.

So what better way than to spend an afternoon sitting at a table opposite this voluble American while he plies you with drinks and tells stories that will shock and awe you, that will drip with the harshness of a people and their surroundings and the history that no one can escape, but underneath there is also a human story of love and lust and that age old conundrum that concerns so many writers: the search for a subject that will satisfy the serious artist. Mr Harsch is well on the way to finding that with this novel whose individual voice will fascinate and entertain the reader in equal measure. Highly recommended and a five star read. ( )

)